“Takin’ it to the Street and Stickin’ it to the Man: Cultural and Political Resistance in Contemporary Sticker Art” – Part I

- Published

- in all

[Note: This blog post is based on the first national paper I gave on street art stickers for the annual College Art Association conference in February 2008 as part of a panel on “The Vernacular Print in Contemporary Art” chaired by Beauvais Lyons. I have updated some of the links and images to reflect more current resources.]

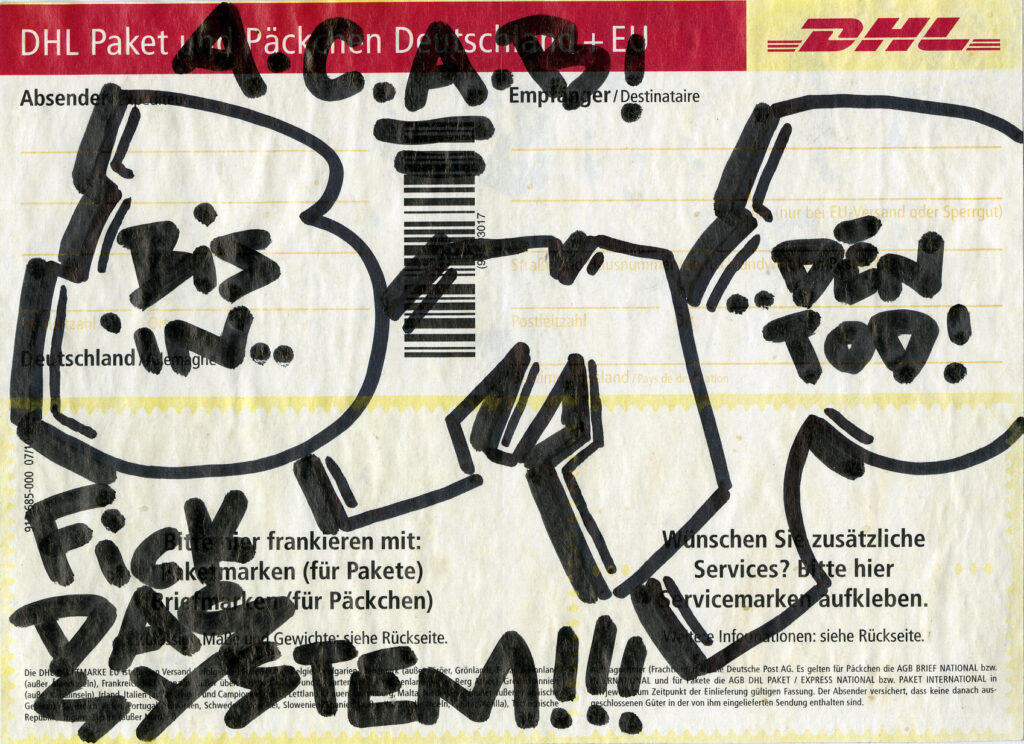

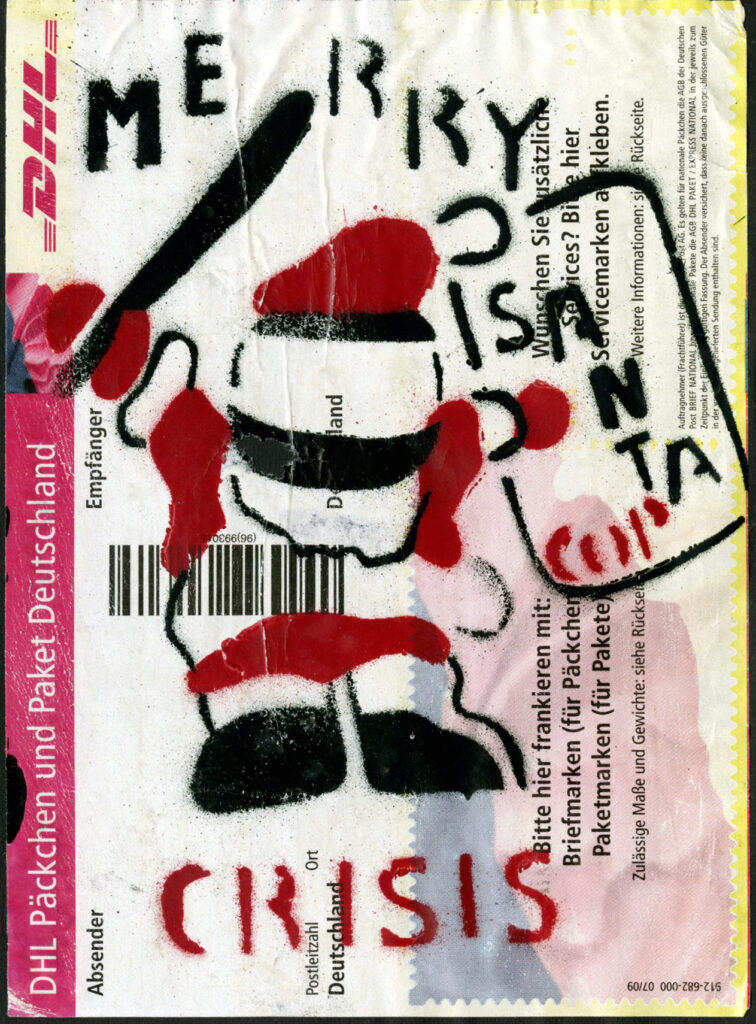

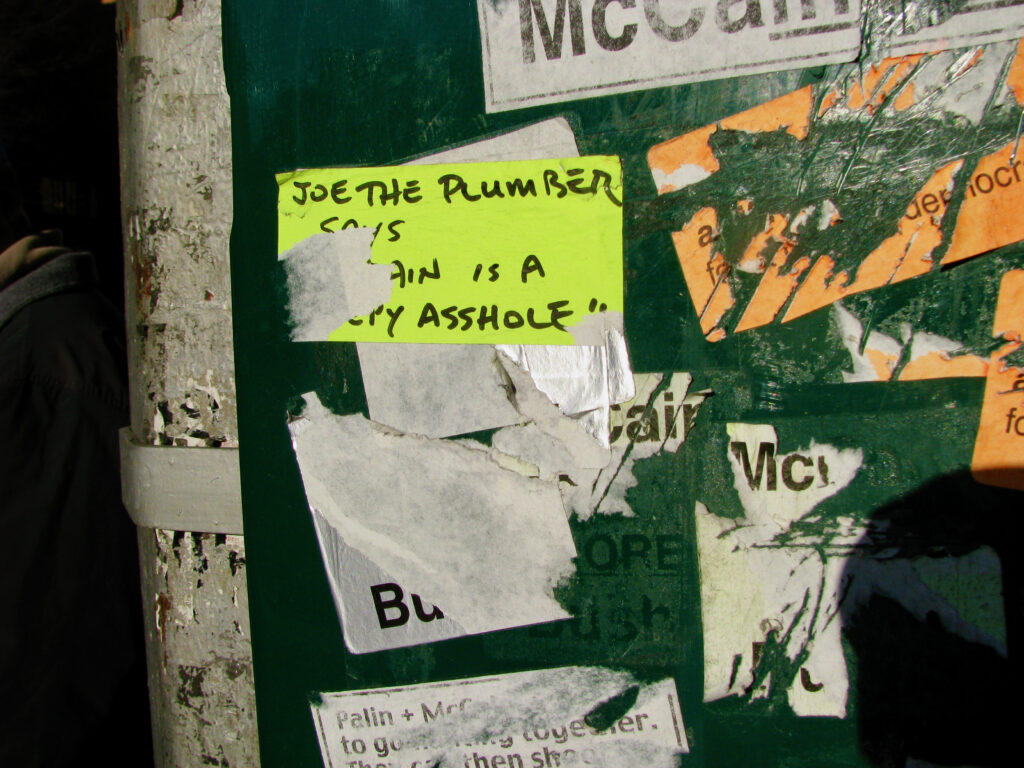

In this paper, I examine contemporary sticker art as a form of cultural and political resistance, using primary examples collected since 2003 from the United States, Germany, and Canada. In the first half of the paper, I provide an overview of the “how, “why,” “who,” and “what” that is communicated in contemporary sticker culture. In the latter half (forthcoming), I discuss specific stickers from Germany and the United States that focus on three broad themes: politics, culture and the media, and the environment.

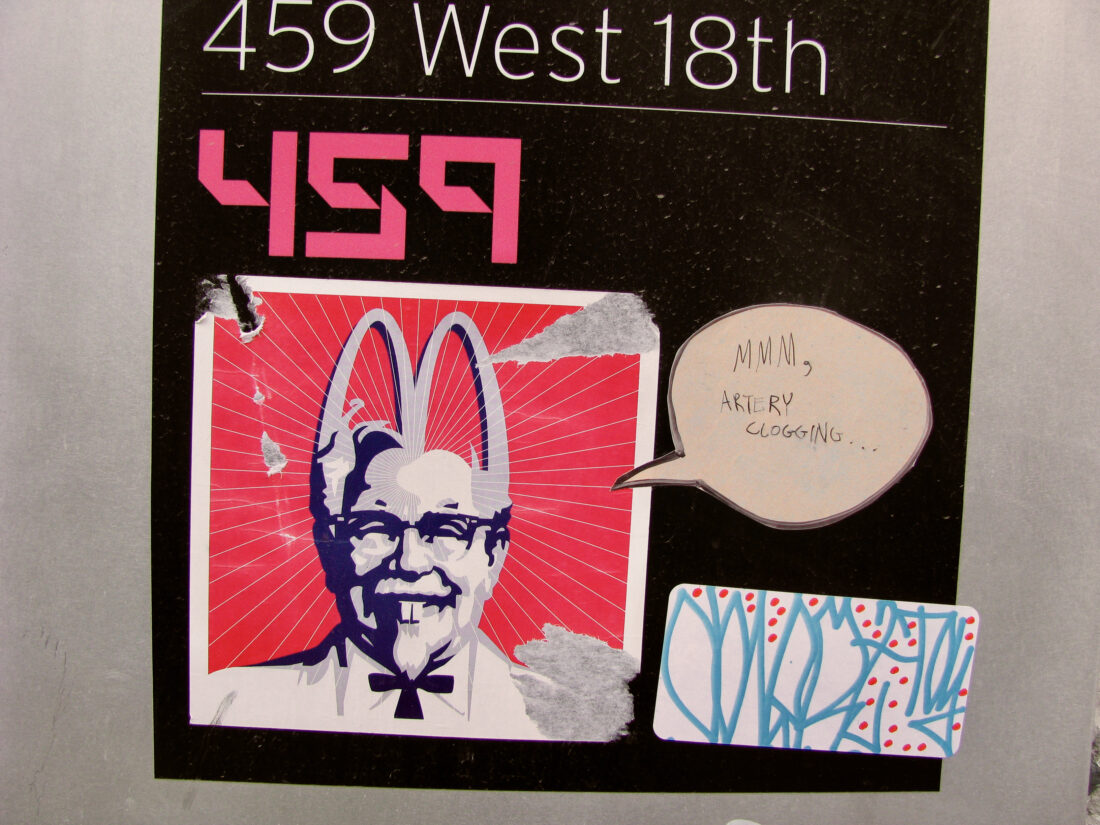

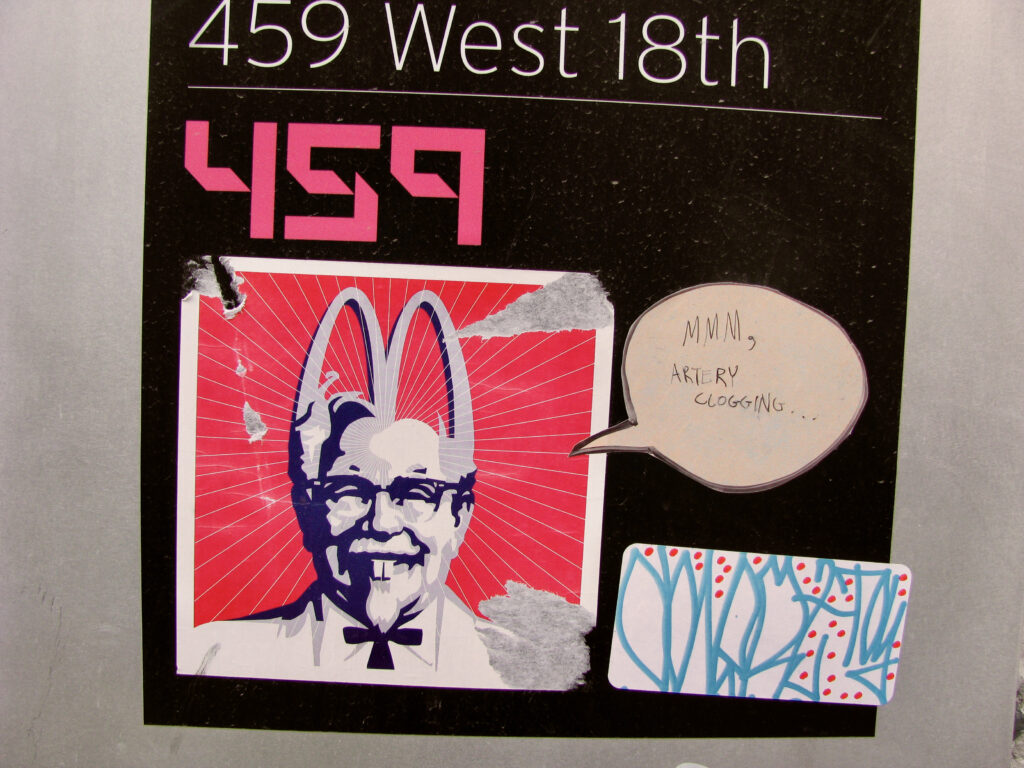

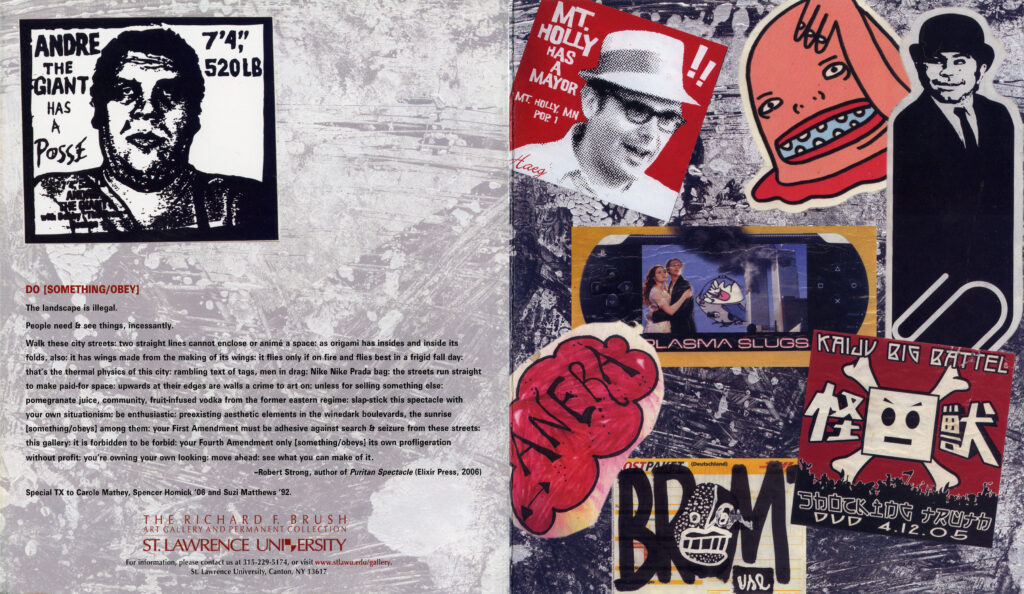

Many of the grouped stickers in this presentation are from an exhibition that I organized in 2006 entitled “The Gallery Has A Posse” for St. Lawrence University, where I work as gallery director. (I’ll explain the “posse” reference later.) I also show images of stickers photographed on site, as well as screen shots from various websites, focusing in particular on the anti-authoritarian, anti-capitalist, anti-commercial, and anti-elitist messages that stickers convey. It’s easy, in fact, to demonstrate that stickers and sticker artists are “takin’ it to the street and stickin’ it to the Man.”

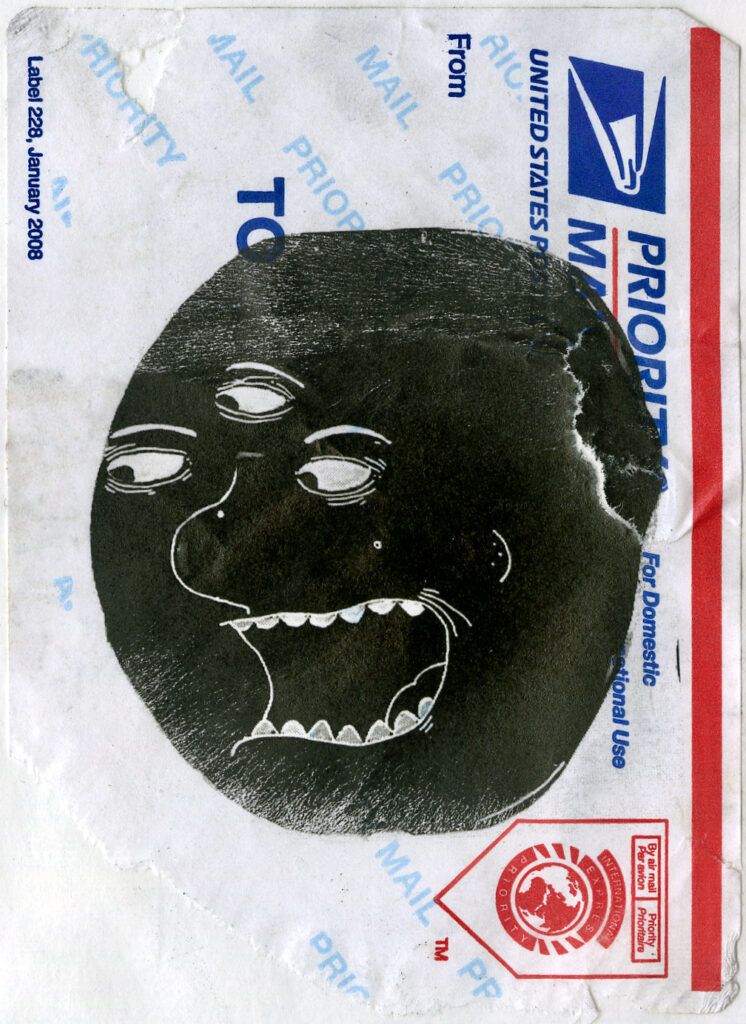

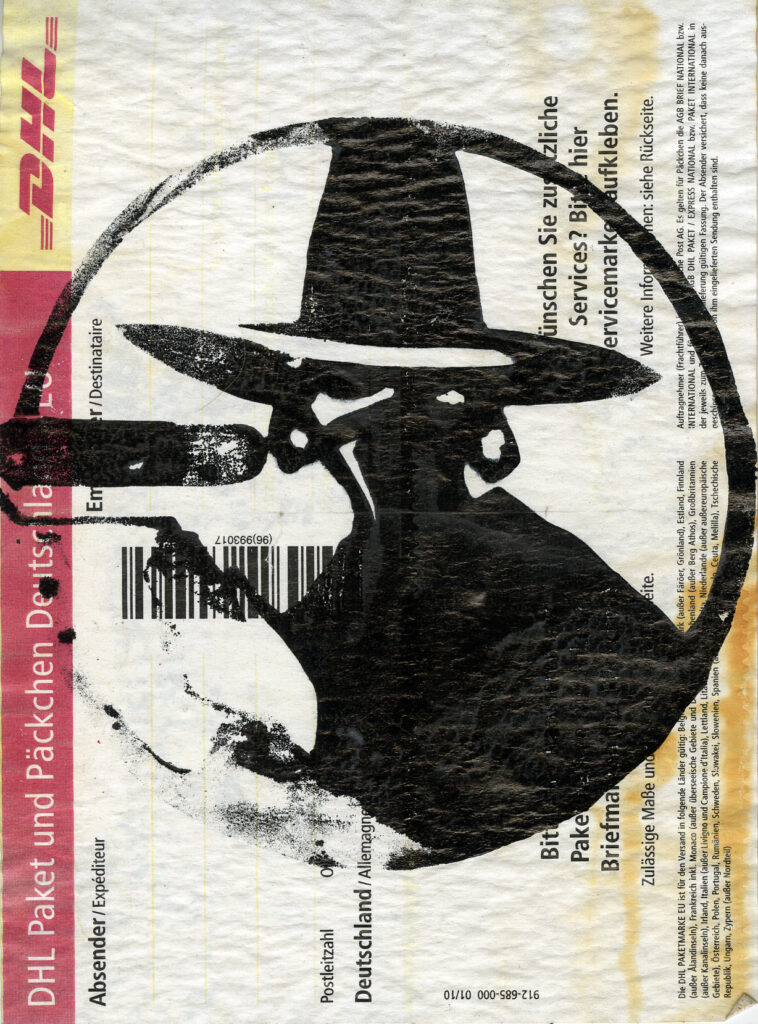

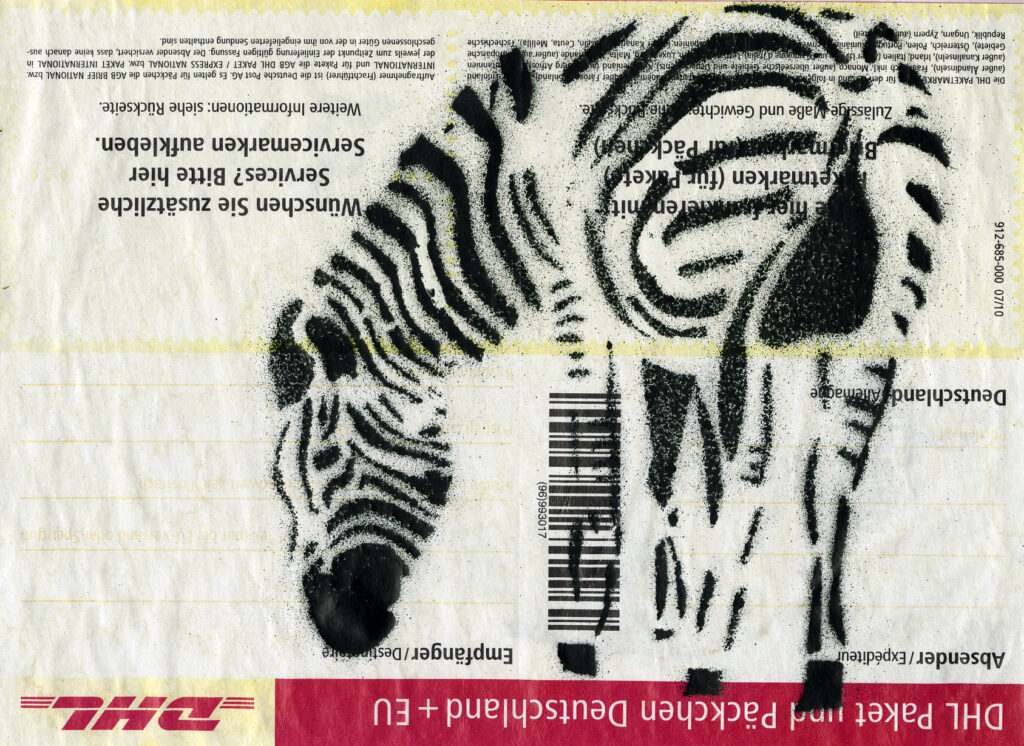

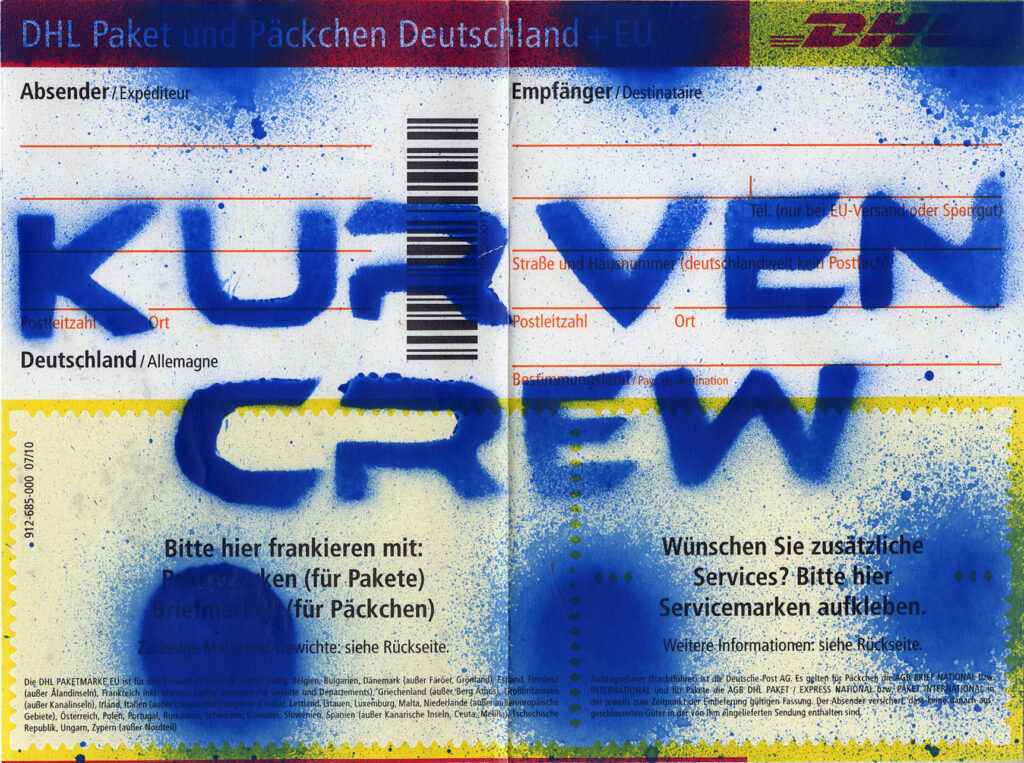

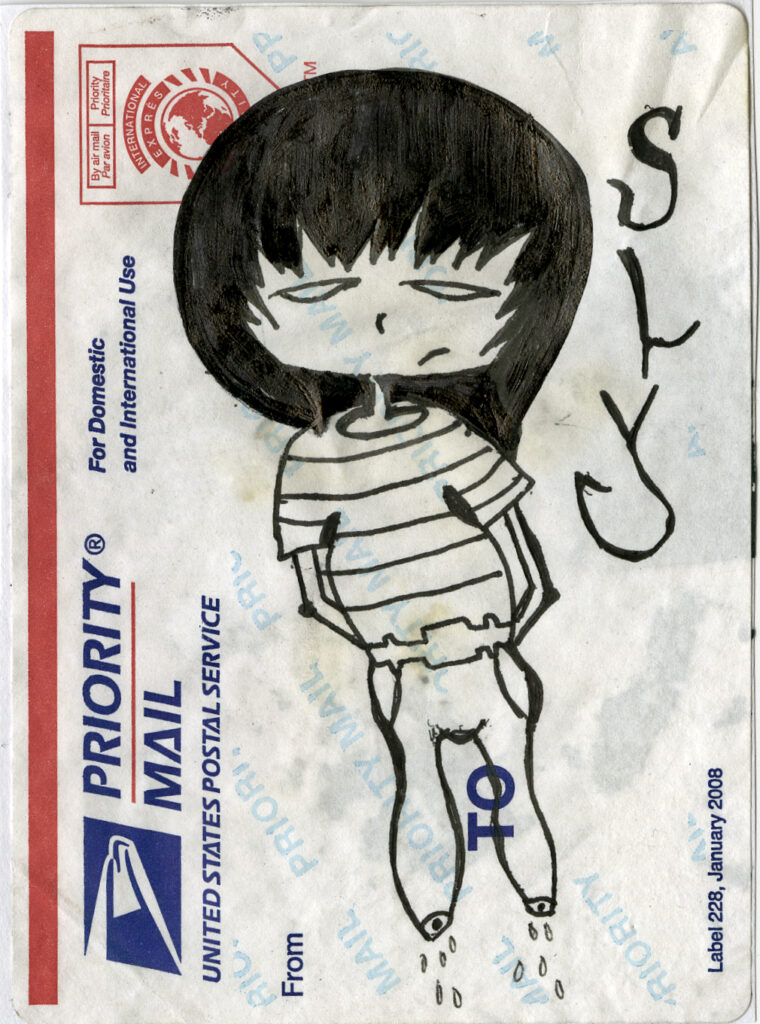

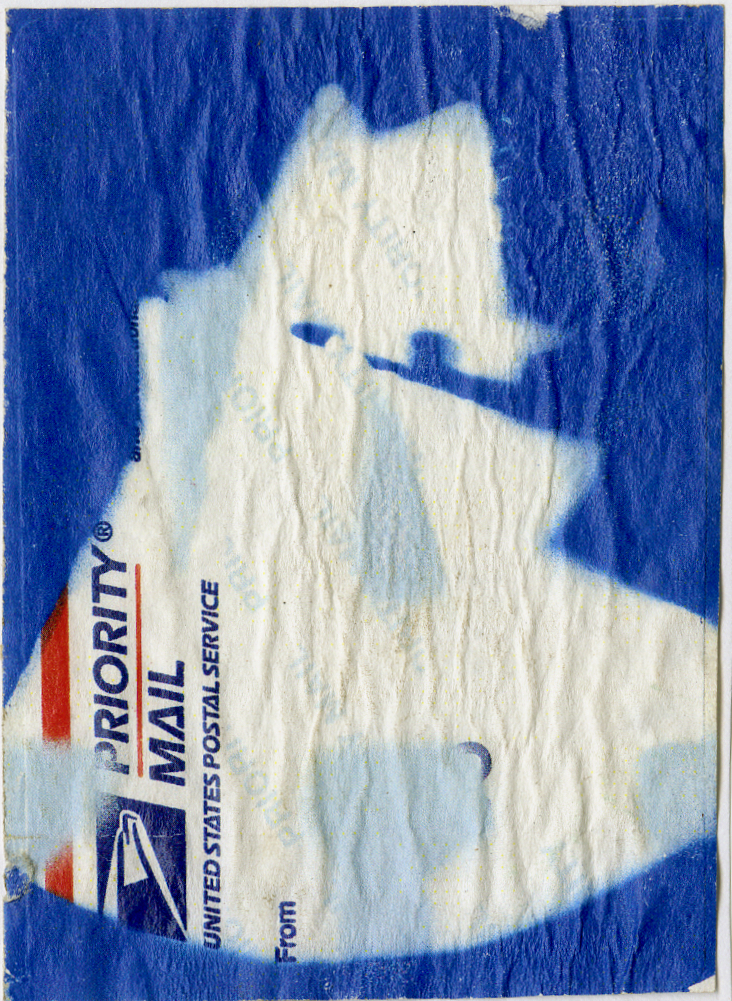

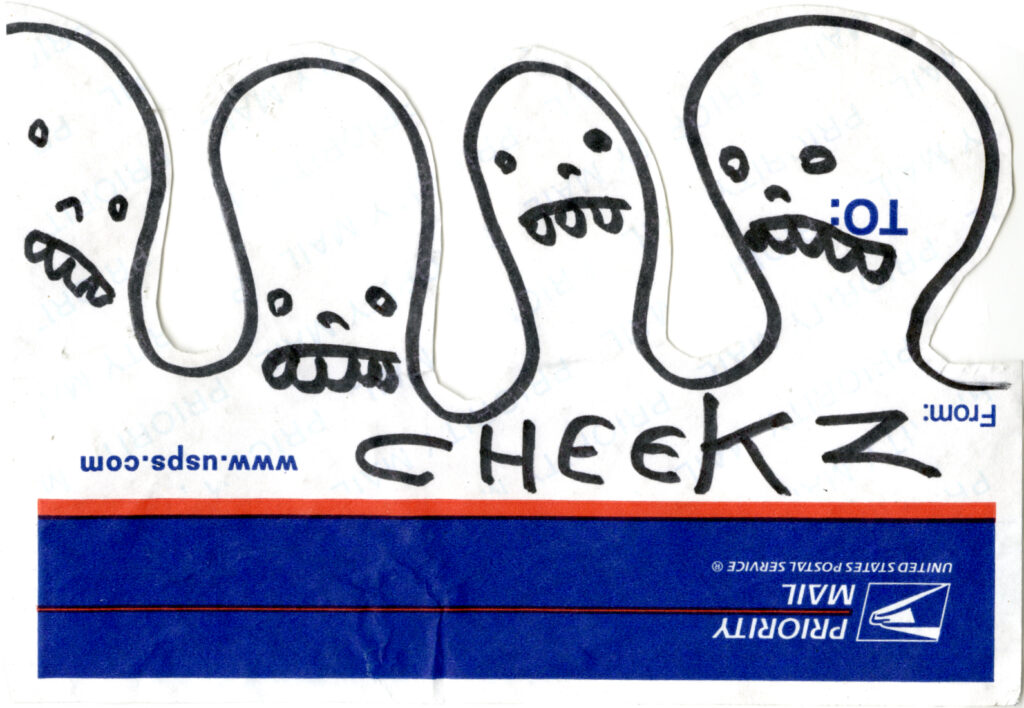

Some of the images I show today might be considered offensive, so please be forewarned. It’s also important to note that I am not discussing typical bumper stickers in this presentation. Rather, these stickers, also called street stickers or art stickers, typically run small in size, around 2×3 to 4×6 inches, or smaller. Premium vinyl stickers can be created easily through fast, cheap online commercial printing services where artists upload a digital file and, within a week, receive a hundred to several thousands of stickers. Such services can be found online through Sticker Robot, StickerNation, and Sticker Guy, among others.

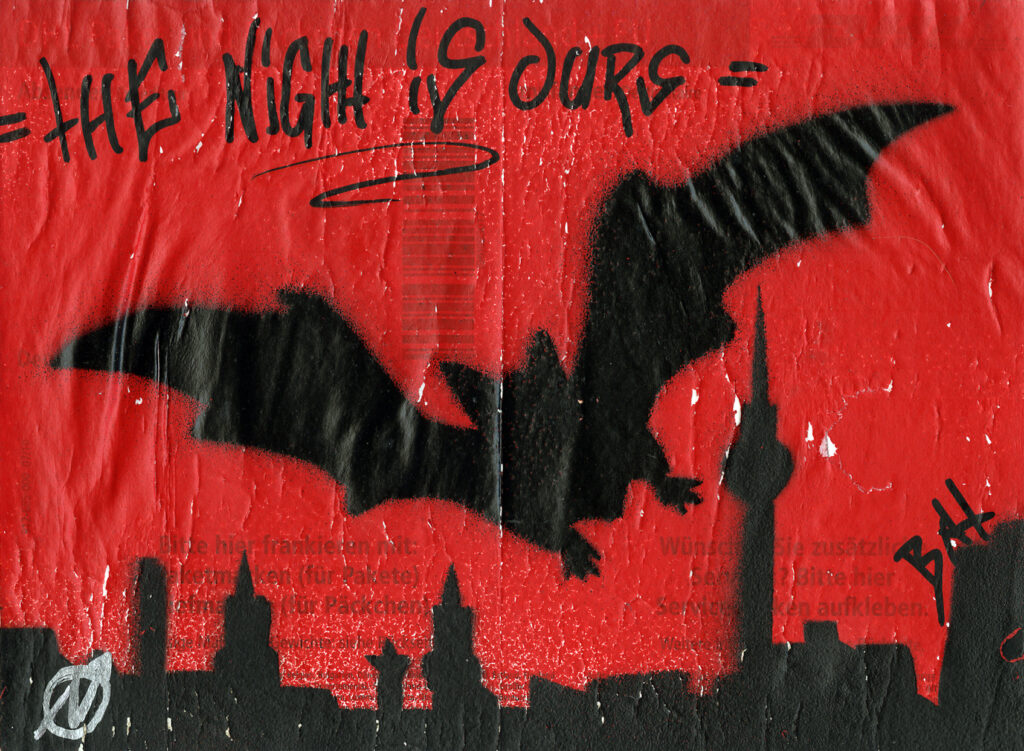

Publicly placed stickers are now ubiquitous in urban centers around the world, situated metaphorically at a busy intersection of imagery and content formed by hip-hop, punk, anarchy, and other forms of “culture jamming,” a term that refers to the process of transforming and subverting mass media. Often seen at eye level or just beyond reach, stickers grace every imaginable surface of the built environment—from light poles and traffic signs to construction sites and dumpsters. Stickers also adorn skateboards, musical instruments, and laptops, appealing to a hip and engaged youth culture and even a middle-aged woman like me.

In terms of naming, sticker artists function much like traditional graffiti artists from the last 35 to 40 years. Crispin Sartwell, while chair of Humanities and Sciences at the Maryland Institute College of Art, wrote,

“Most graffiti artists dub themselves with the name they use in their work. In part, this is an attempt to undermine the use of names, [both] in the legal system and [in] modes of surveillance: to create a persona that worms its way underneath the forms of textual power. The idea is simultaneously to be hard to identify by power and massively famous outside it: to manufacture an unofficial name that does not appear on [a] birth certificate or other documents and then to broadcast it as far as [possible] in a culture underneath the official one.”

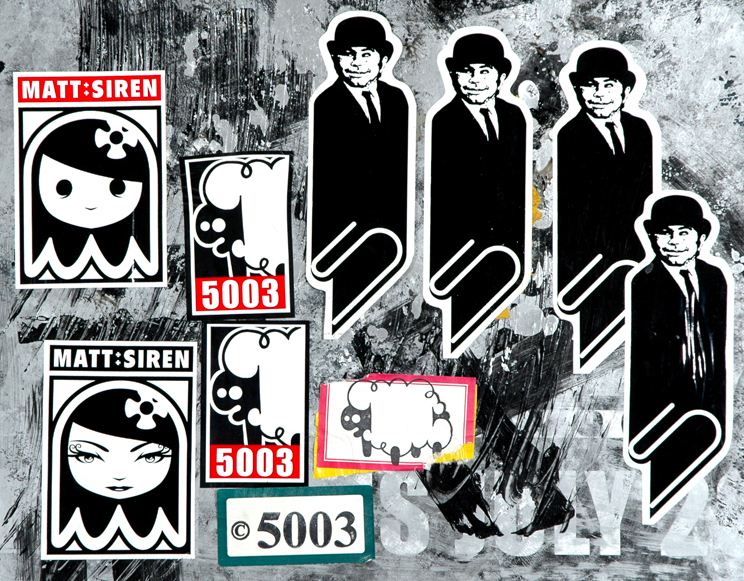

Nowadays, many sticker artists don’t identify themselves with a name per se, but bomb the streets with personal avatars like humanoid figures, robots, sheep, bunnies, hands, faces, four-leaf clovers, ants, flies, or plant forms. Aside from overtly political stickers, portraiture and signature stickers are among the most common forms of expression, whereby artists are tirelessly engaged in a D-I-Y form of self-promotion. As such, many artists use stickers as a means of “tagging” a public space, making it one’s own, at least temporarily. Examples here from the mid-2000s include Obey Giant, Faile, 5003, RobotsWillKill, orkid man, Hek Tad, and Matt Siren.

In this context, tagging is a way of “hitting” a site. In a 1974 essay entitled The Faith of Graffiti, Norman Mailer, functioning in the role of new journalist, wrote,

“You hit your name and maybe something in the whole scheme of the system gives a death rattle. For now your name is over their name, over the subway manufacturer, the Transit Authority, the city administration. Your presence is on their presence; your alias hangs over their scene. There is a pleasurable sense of depth to the elusiveness of the meaning.”

Here Mailer describes the satisfaction of stickin’ it to the man, and his analysis is further revealed in an interview with “Cay” and “Junior 161,” two young street artists who, when asked about the significance of naming, declare, “The name is the faith of graffiti.” Organizers of a recent Berlin-based sticker exhibition also elaborate upon Mailer’s revelation,

“…unlike graffiti, […] stickers don’t have the gesture of destruction inherent in their form – [rather, they are a] gesture of connotation and satiric annotation. [Sticker] interventions are much more representative for a critical mind seeking to contribute to the social urban exchange….”

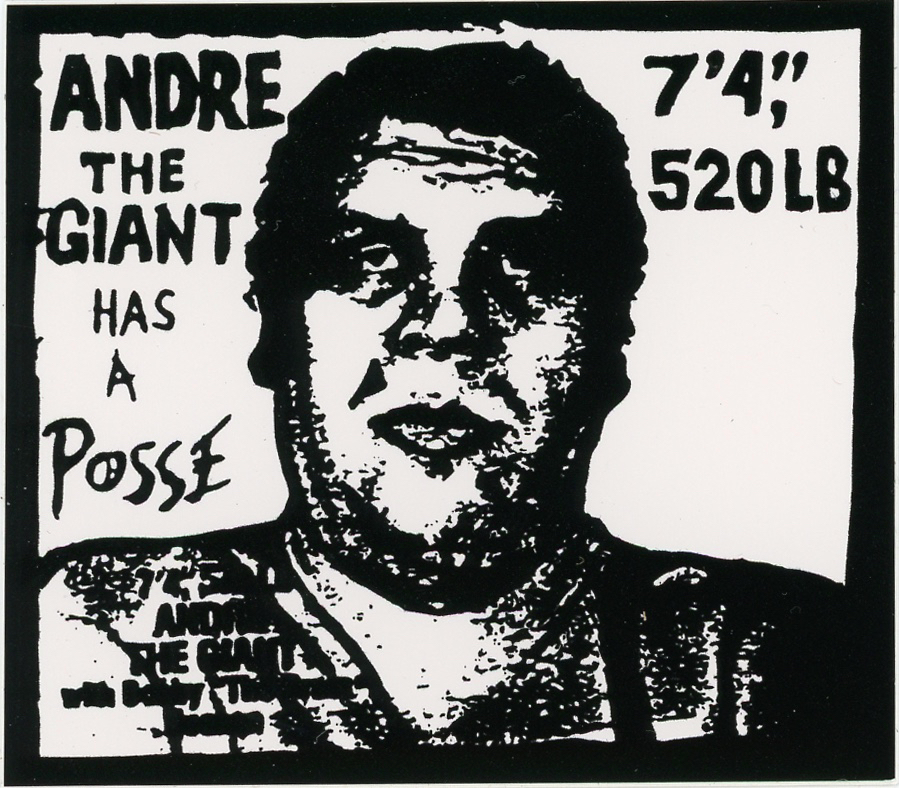

Fast forward to 2008. Stickering is a now a global phenomenon. Shepard Fairey’s Andre the Giant Has a Posse sticker, designed in 1989, is best-known in every counter-cultural context (and by now in many mainstream contexts), as are scores of variations in his ongoing, international “OBEY Giant” propaganda campaign.

In addition, hundreds of Obey Giant bootleg stickers reference the original Andre the Giant design, but feature a range of subjects, from “Charles Darwin has a Posse,” for example, to Vinny Raffa, the Dalai Lama, Emily the Strange, movie stars, serial killers, family members, and pets.

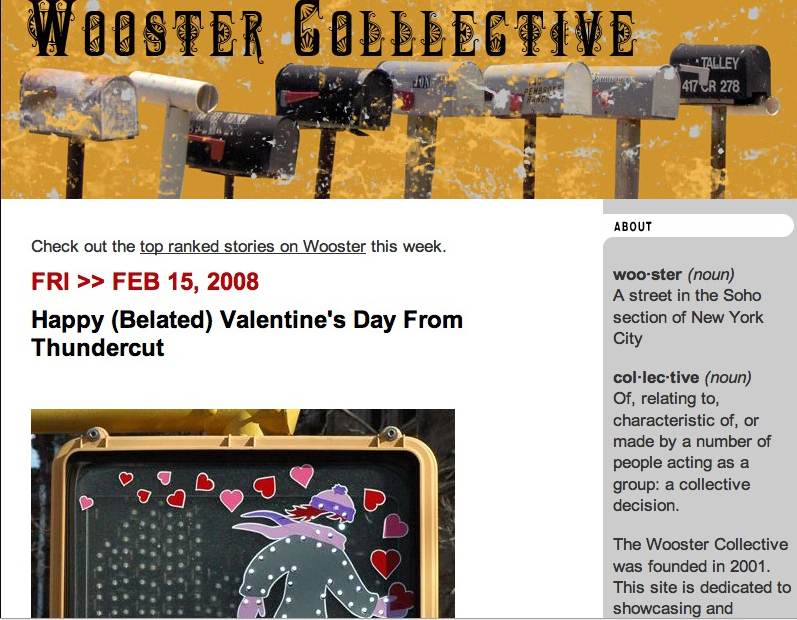

Sticker artists, like other street artists, often project themselves as underground art activists and maintain a kind of guerrilla or gangsta’ profile on the street and online, posting on Websites and blogs, such as the Wooster Collective, PEEL Magazine’s SLAPS Stickerhead Forum, BOMIT, and several other international sites. [Note: many of these websites no longer exist in their original iterations.]

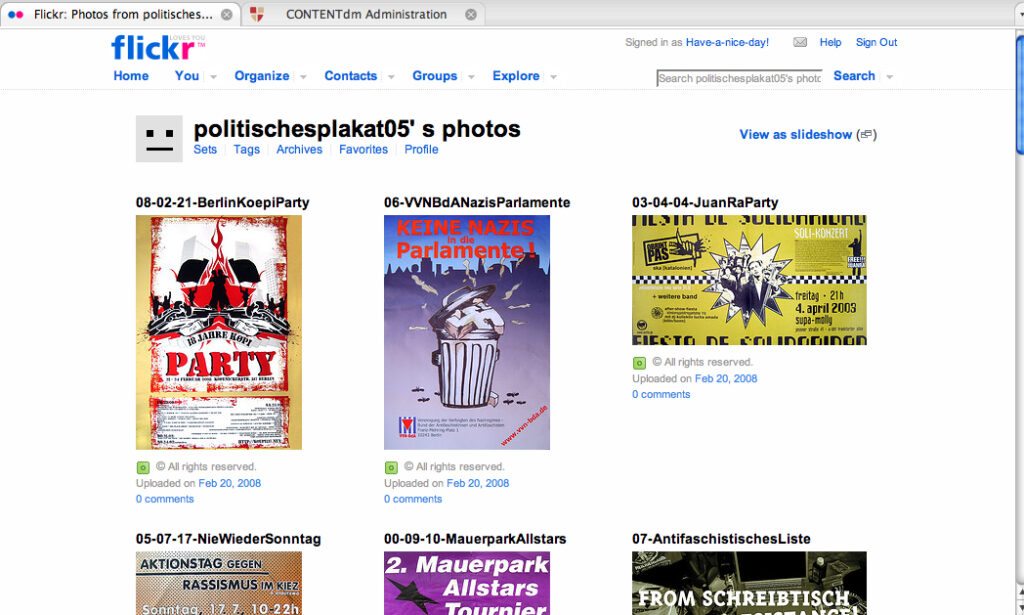

The web also serves as a means for artists to distribute their works. By posting and attaching image files of their stickers on social media like Flickr and elsewhere, artists make it possible for others to print and post their imagery in almost any location.

Flickr and other social media sites also provide a way of “tagging” images, where an online community of tens of thousands of viewers discuss and tag sticker photographs. Such “folksonomic” projects, which incorporate user-generated content or metadata, ironically subvert the elaborate structures of authority lists and controlled vocabularies that are the foundation of most institutional digital image collections. Dr. Jill Walker from the University of Bergen, Norway, describes this as a form of “distributed narrative,” in which time, space, and authorship are not unified, but are rather what she characterizes as being “across media, through the network, and … in the physical spaces that we live in.” I call this hybrid mix “Street Art 2.0.”

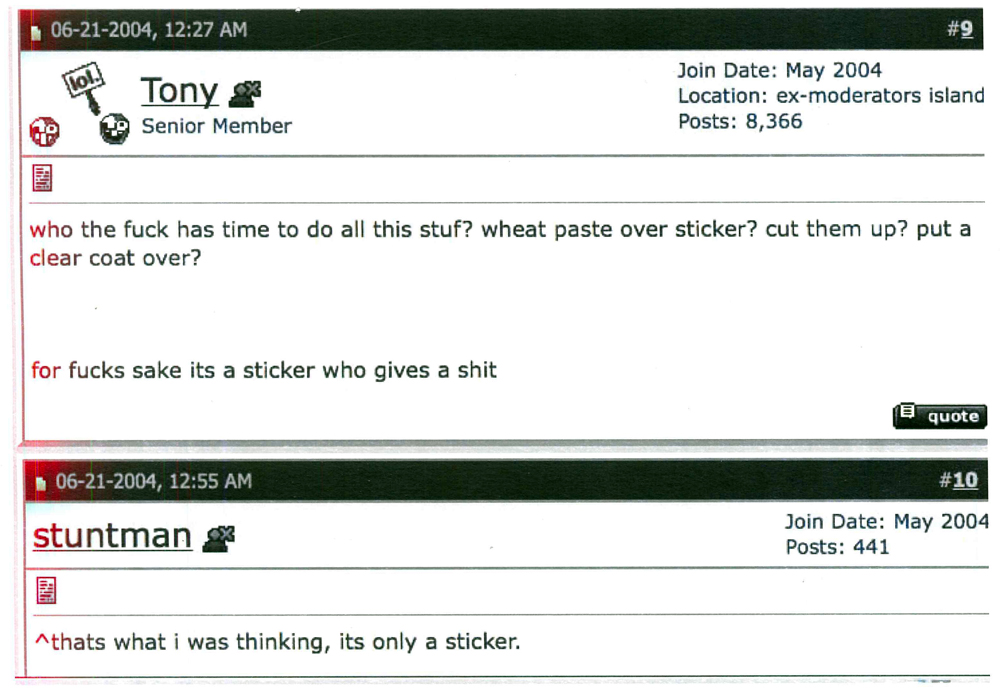

In keeping with their rebellious persona, many artists reject cultural co-optation by avoiding certain mainstream settings in order to keep their activities “on the streets.” Two years ago, for instance, I posted a request on an online “Stickerhead Forum,” asking if anyone would like to send me stickers for the exhibition I was organizing at St. Lawrence. I naively put “cathytedford” as my username and included the name of the gallery at SLU. Not surprisingly, one artist, “delOR,” chided me in response by posting, “keep it gangsta, and on the streets.” Another artist named “Zen” wrote back, too, stating, “the whole idea is not to ask… it’s to do… teacher man… that’s what makes the difference, your asking about it. Just do it. Like Mikey.” Chuckling to myself, I realized at the time that I had become a female version of the Man! However, a young artist from Queens called “Plasma Slugs” eventually contacted me and came to campus to talk about his work and make stickers with students. I think it was the first time he’d ever filled out a W-9 tax form.

Crispin Sartwell. Graffiti and Language. http://www.crispinsartwell.com/grafflang.htm. 2004 [Note: website unavailable in 2021.]

Kurlanksy, Mervyn and Jon Naar. The Faith of Graffiti. (NY: Praeger Publishers, 1974).

“THE ABC: power and communication/the semiotics of resistance” exhibition organized by Rebel:Art Media Foundation and Memefest, Neurotitan comic store and gallery, Berlin, 2005. See http://www.theabc-org. [Note: website unavailable in 2021.]

Walker, Dr. Jill. “Distributed Narratives: Telling Stories Across Networks.” Presented at AoIR 5.0, Brighton, September 21, 2004.