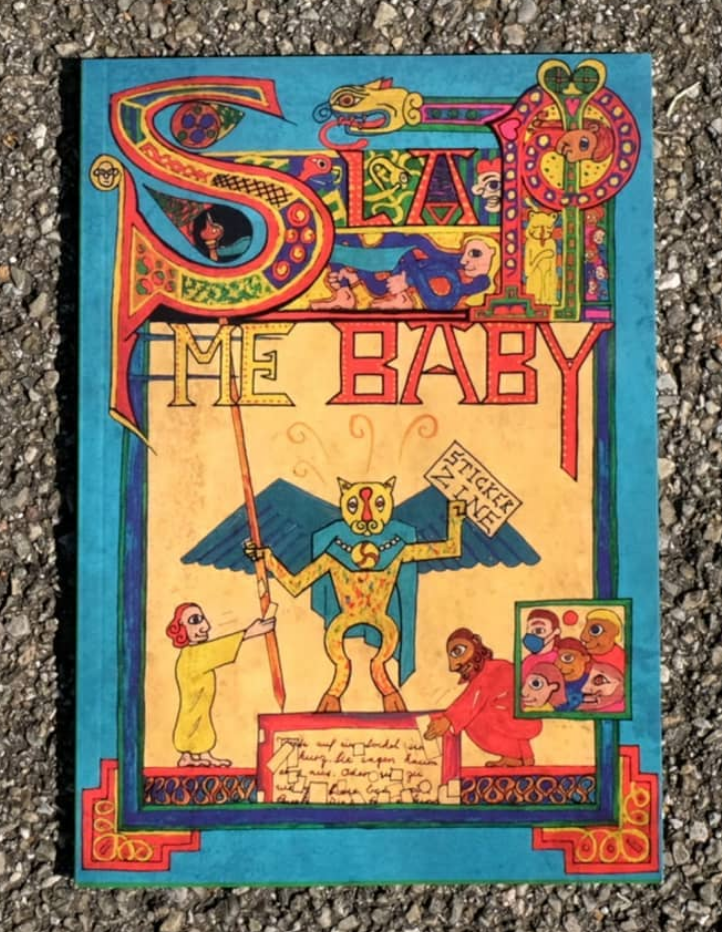

“Slap Me Baby” interview

- Published

- in all

Folks from the Slap Me Baby sticker collective in Switzerland contacted me in the spring of 2020 to submit an essay on I.W.W. “stickerettes” and to respond to some interview questions for their next zine. They also sent me some great artists’ and political stickers, which are in the queue to be scanned and catalogued into the Street Art Graphics digital archive. Zine #3 can be purchased on the Slap Me Baby website here.

I read the interview again today and decided to publish it on Stickerkitty, too.

Can you describe in short words how your interest in stickers began and how it found its way into your academic work?

I first discovered publicly placed stickers while visiting Berlin in 2003. It changed my entire relationship to that city and to every other city I’ve ever visited since that time. I have spent hundreds, probably thousands, of hours roaming around cities looking for stickers. At the time, I also initiated a digital archive at the university where I work as gallery director in order to catalogue what I was finding, and for teaching and research. Many students have helped with the project over the years. I’ve integrated stickers into the curriculum through class discussions, traveling exhibitions, lectures, and hands-on workshops. You can read more about the archive on the Artstor Blog.

Are there countries, regions or cities that you think have an outstanding sticker culture?

Hands down, yes, Berlin is unparalleled in terms of a thriving sticker culture, as are parts of NYC and Montreal, the latter of which are both geographically close enough for me to make regular trips to look for stickers (at least before the pandemic). Berlin and Montreal are both cities marked by conflict and struggle, which affects what you see in the streets.

What distinguishes the sticker in public space from the countless images we see day by day in the feeds of online platforms?

The images found online are all mediated and equalized by the screen. Stickers in real life have materiality and texture. Paper stickers are different than vinyl stickers. Hand-drawn postals are different than stenciled or commercially printed stickers. Stickers have personalities. Some shout; others whisper. Stickers are made by real human beings who have something they want to communicate to the world around them.

Is there a “danger” of an institutionalization of the sticker game, similar to what happened to graffiti with commercial street art, or do you see a chance in it?

As someone who has organized sticker exhibitions, i.e., taking stickers out of their original context and putting them into galleries, I see how that changes the meaning and intent of stickers. I don’t see it as a problem, however. It’s just different. Students who visit the sticker exhibitions love them. Artists have also been keen to get involved. It’s important to acknowledge the context in which stickers are made and viewed, and to avoid any sort of commercialization. I do my work in an educational, non-profit environment, which makes a big difference.

Do you have one or more personal favorite artists who make stickers?

I love just about every sticker I come across, to be honest, but I’m really drawn to one-of-a-kind handmade stickers. They’re usually so earnest. Or mischievous. Or silly. It’s all good.

We have the impression that there are more female artists who make stickers than in graffiti. Do you share this impression?

I’m more familiar with stickers than with the graffiti world, but I know that Montreal’s Under Pressure graffiti festival in August every year has made it a point to feature female artists. My friend Oliver Baudach at Hatch Kingdom in Berlin has also done a wonderful job for years working with female sticker artists. We recently organized a traveling exhibition called She Slaps: Street Arts Stickers by Women Artists From Around the World.

What will the Stickergame look like in 20 years? Do we have to expect major upheavals, new technical possibilities, increased acceptance, stronger repression or something completely different?

That’s a great question. I’ve wondered that, too, since I’ve been stickering for the past 17+ years. I think the motivation and reason to make stickers will continue. It’s the neighborhoods that will change, usually due to urban development and gentrification. Certain parts of Manhattan in the early 2000s were peppered with stickers. Today, those same streets have been stripped clean in favor of luxury condos and shopping centers. But sticker artists will find other places to share their creations. They are unstoppable.