Early history of I.W.W. “stickerettes” or “silent agitators”

- Published

- in all, Stickerettes

[Note: a shorter version of this essay first appeared as “Silent Agitators: Early Stickerettes from the Industrial Workers of the World” in Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture. Volume 6 (February 2018), PM Press. See also the timeline I put together of early advertisements and newspapers articles about I.W.W. stickerettes.]

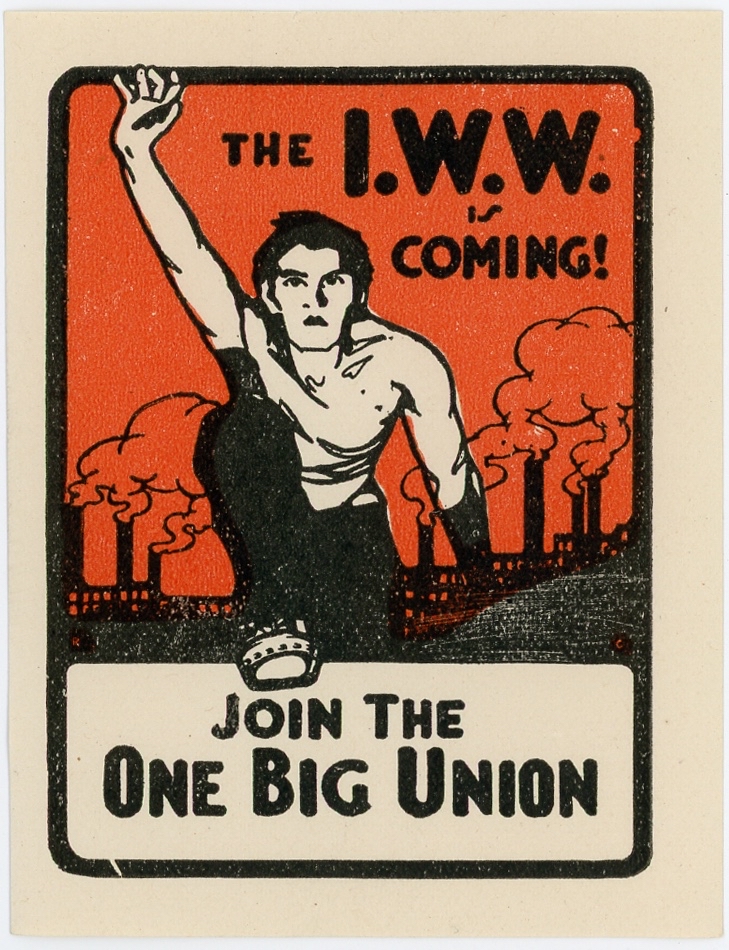

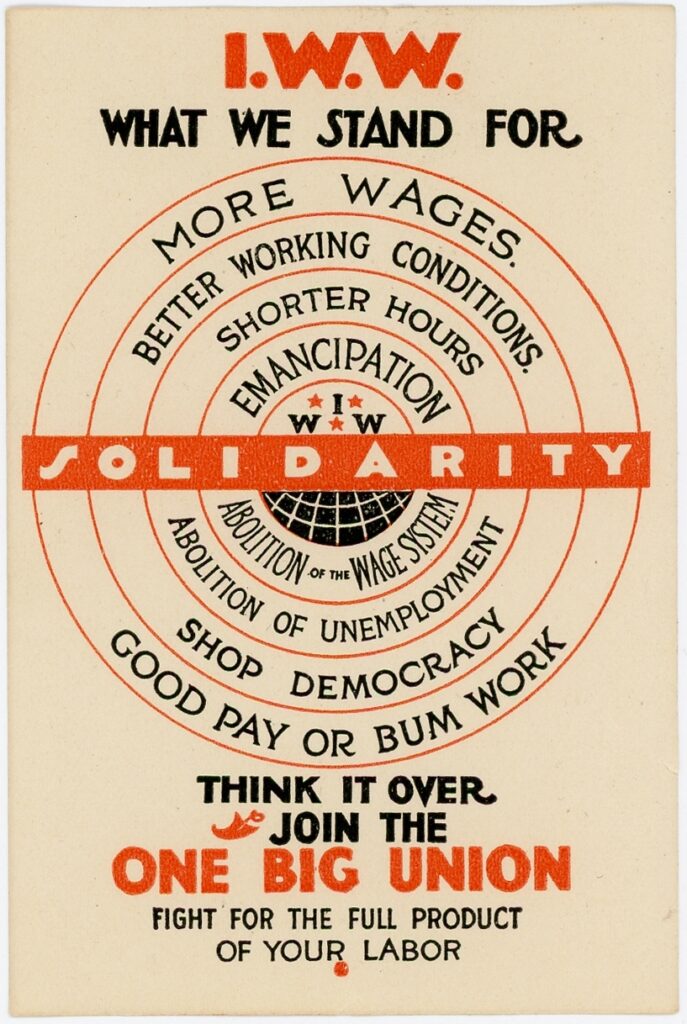

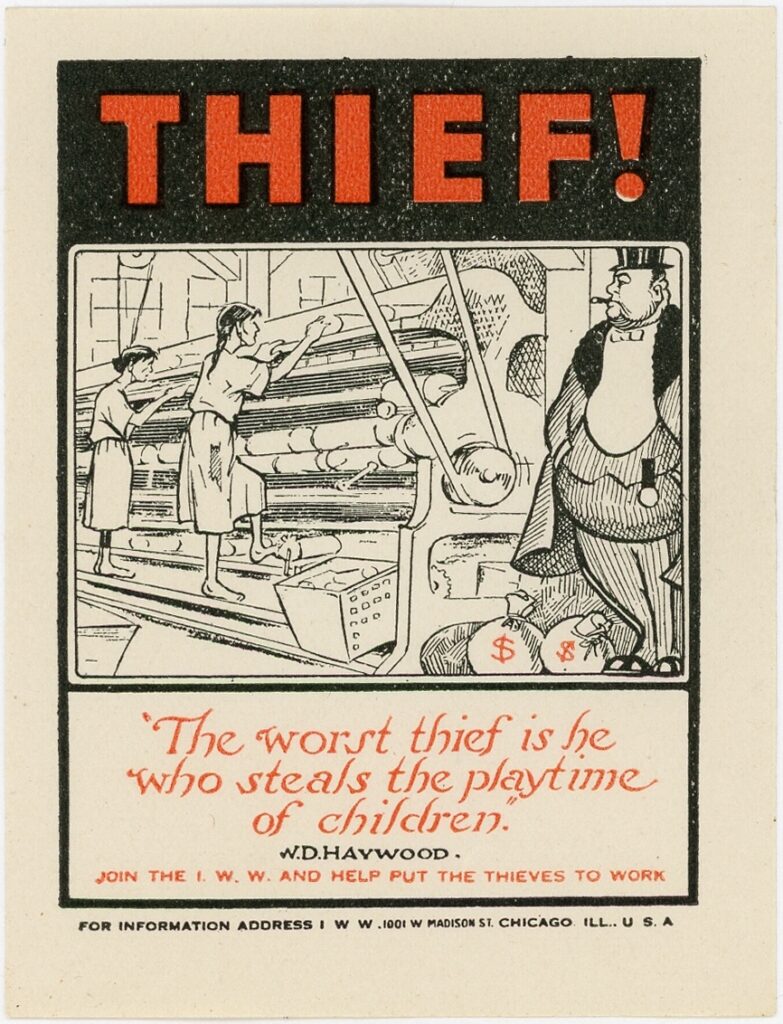

Founded in Chicago in 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W. or “Wobblies”) fought for economic justice for the working class using many tactics, including the widespread use of cartoons, slogans, leaflets, poetry, and songs that appealed to uneducated, immigrant, and itinerant workers. As early as 1906, the I.W.W. began producing political stickers to promote the vision of the “One Big Union” to recruit new members, oppose unfair working conditions, intimidate bosses and strikebreakers (or “scabs”), and condemn capitalism.

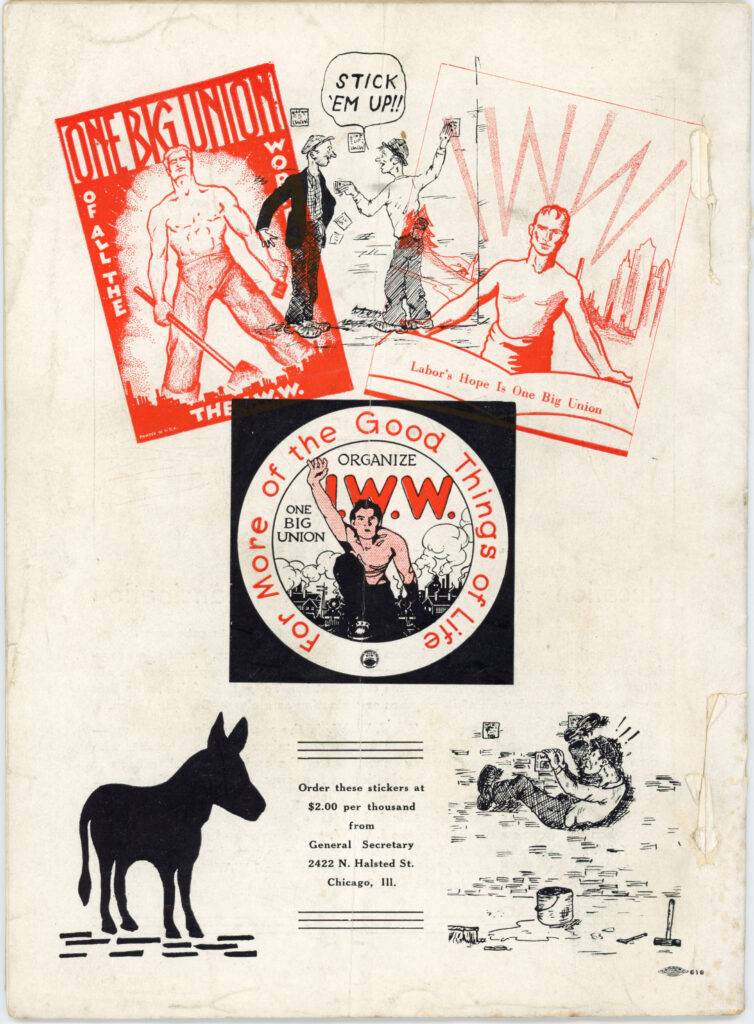

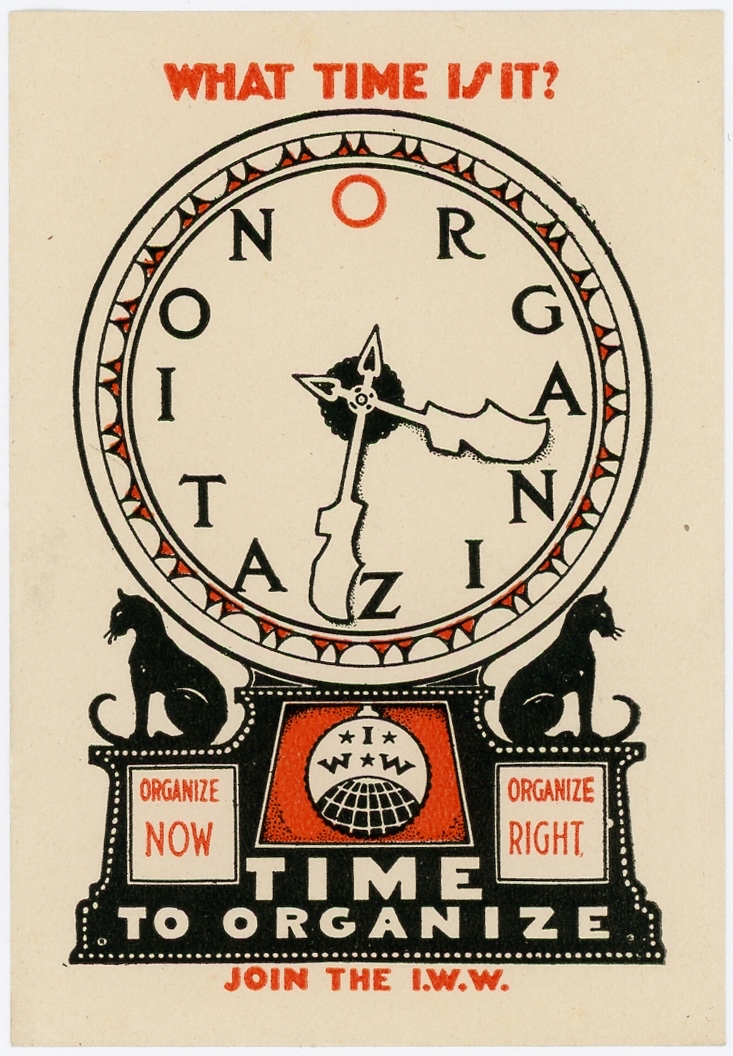

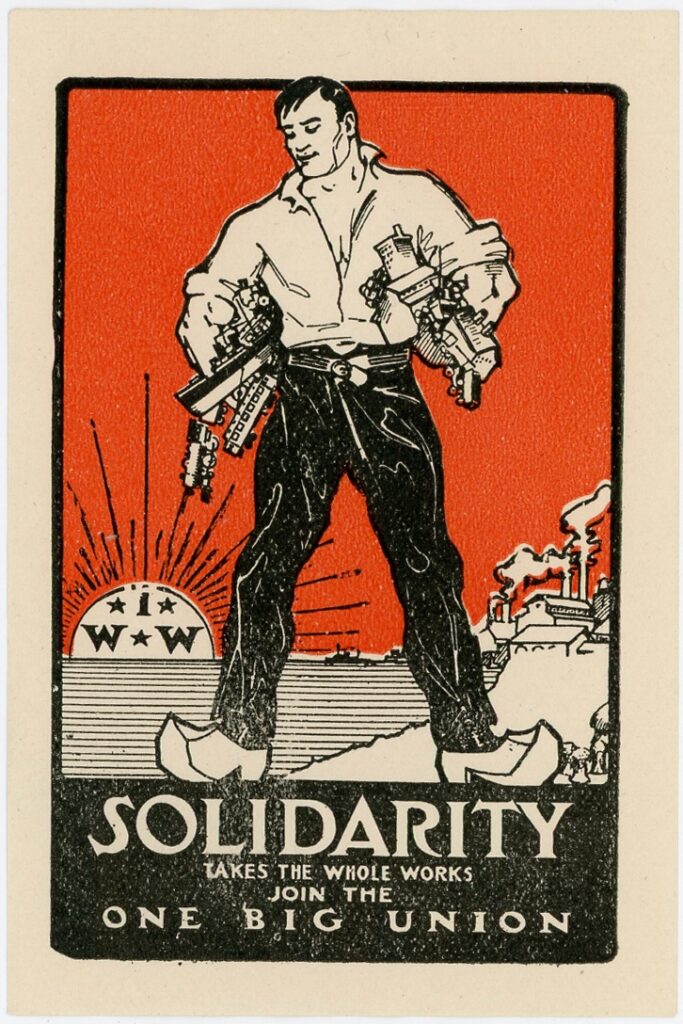

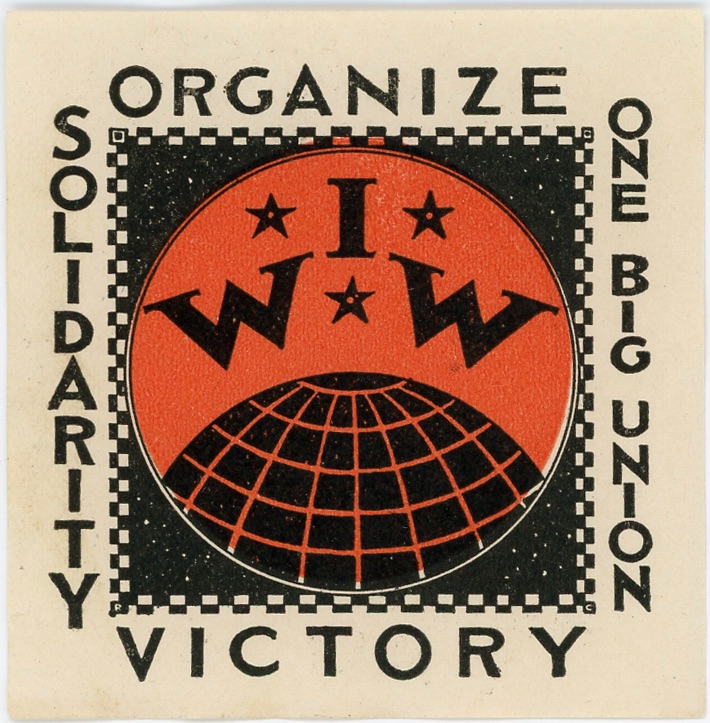

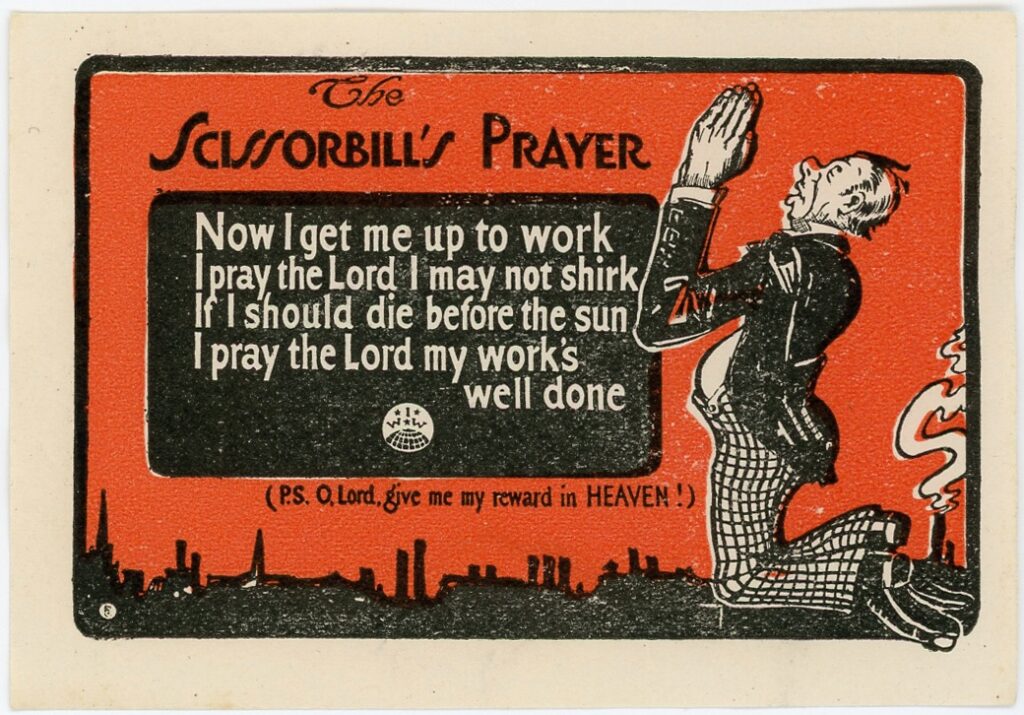

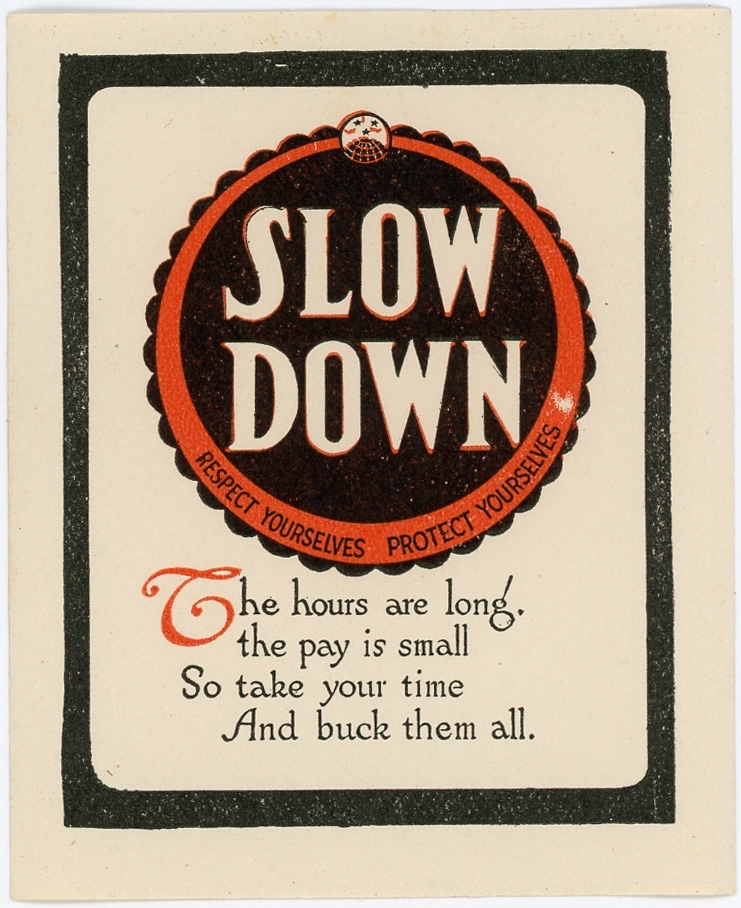

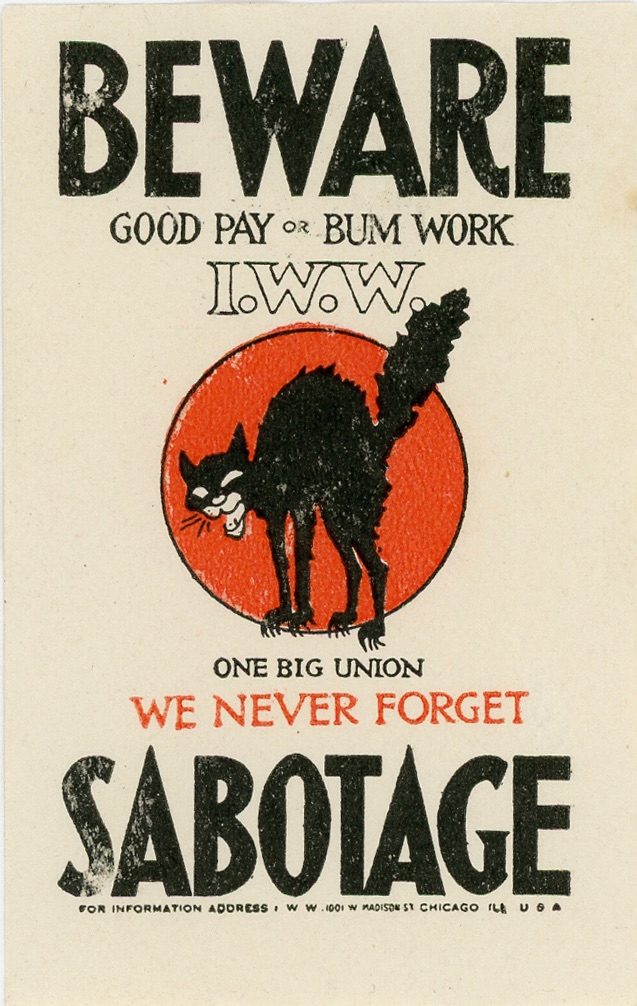

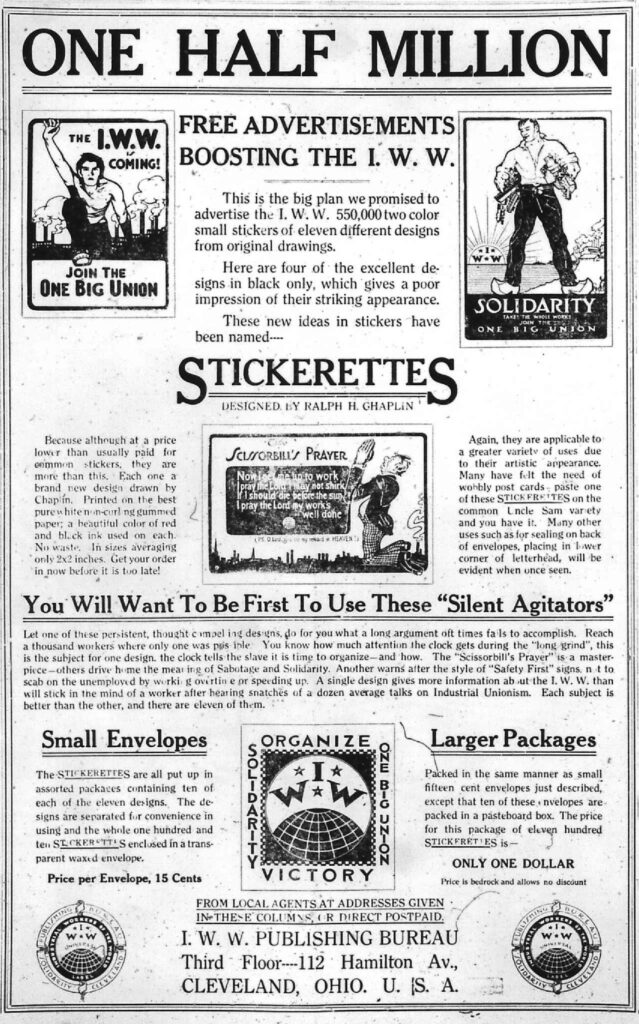

Known as “silent agitators,” I.W.W. stickerettes were printed in red and black on lightweight gummed paper measuring from 1½ x 2 inches to 3 x 4 inches. Inspired by commercial advertisements, the designs incorporated catchy slogans and striking visual graphics that were both elegant and easy to understand. “What Time Is It? Time to Organize!” shouts a clock. “Solidarity Takes the Whole Works,” depicts a Paul Bunyan-sized laborer with an armload of trains and factories. The three stars of the One Big Union (Organize, Solidarity, Victory) wink over the earth. A “scissorbill”—a working man without loyalty to the class—kneels on bony knees and prays to the sky, “Now I get me up to work, I pray the Lord I may not shirk.”

One of the most well-known images, “BEWARE/SABOTAGE,” depicts a hissing “sab cat” or “sabo-tabby” with arched back and claws extended, silhouetted by a blood red moon. The black cat was commonly used to represent sabotage on the job as a means to “frighten the boss.” The labor folklorist Archie Green explains that “the black cat is an old symbol for malignant and sinister purposes, foul deeds, bad luck, and witchcraft with countless superstitious connections. Wobblies extended the black cat figure visually to striking on the job, direct action, and sabotage.”

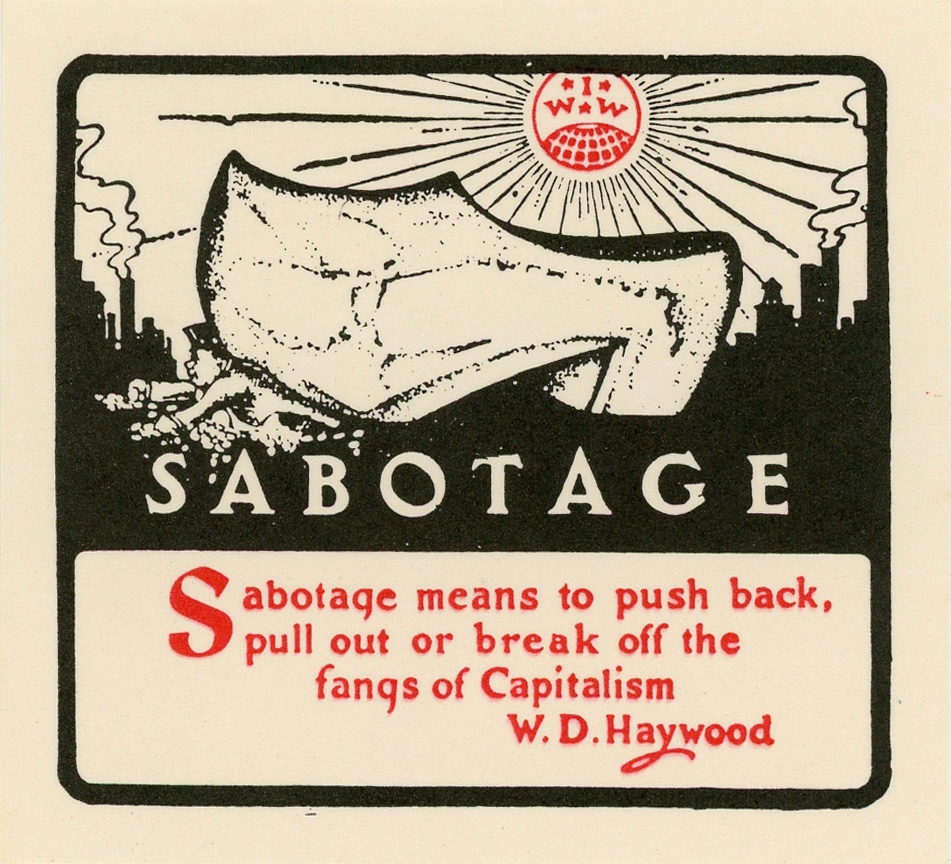

Sabotage is also represented in the stickerettes with the image of a large wooden clog or “sabot” crushing a fat capitalist grasping for coins (sabot, the French word for clog, is the root word for sabotage as workers during the Industrial Revolution allegedly threw clogs into machines as a way to hinder production).

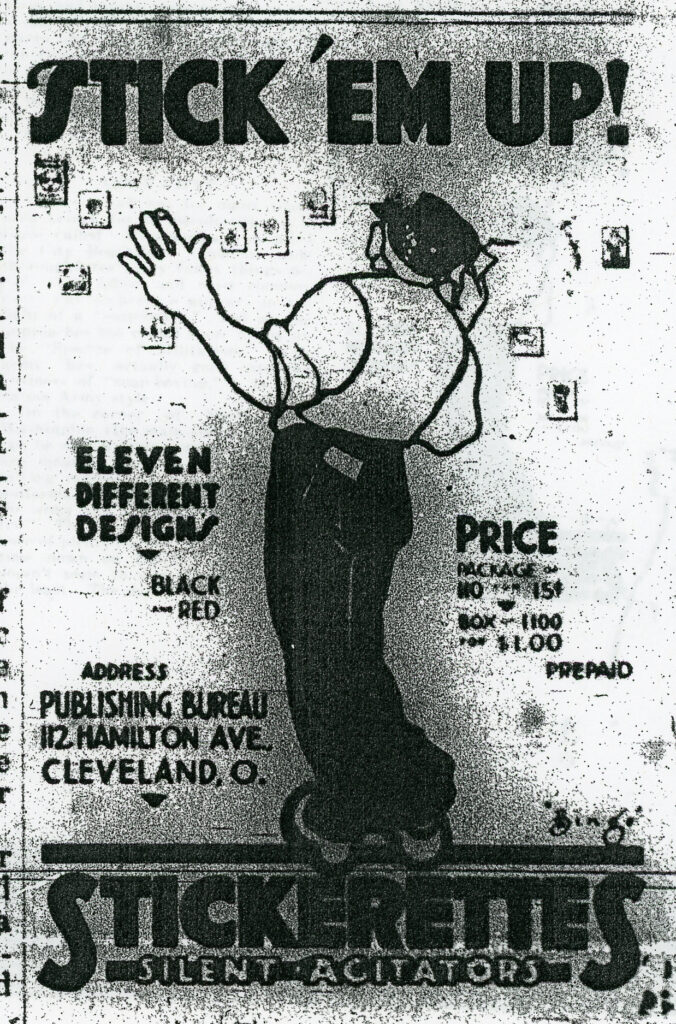

The I.W.W.’s weekly newspaper Industrial Worker first advertised “stickers” in 1911, offering 1,000 for $1.00. During a more ambitious effort a few years later, advertisements in the weekly newspaper Solidarity featured a new series of eleven different designs for $1.00 per box of 1,100 (1915-1916).

The newly dubbed stickerettes gained popularity quickly; between 1915 and 1916, a million stickerettes were printed by the I.W.W and distributed across the country, often by workers traveling from job to job. In March of 1917, a second series of fifteen stickerettes with four new designs was advertised for the same low price. A million stickerettes sold out within two months.

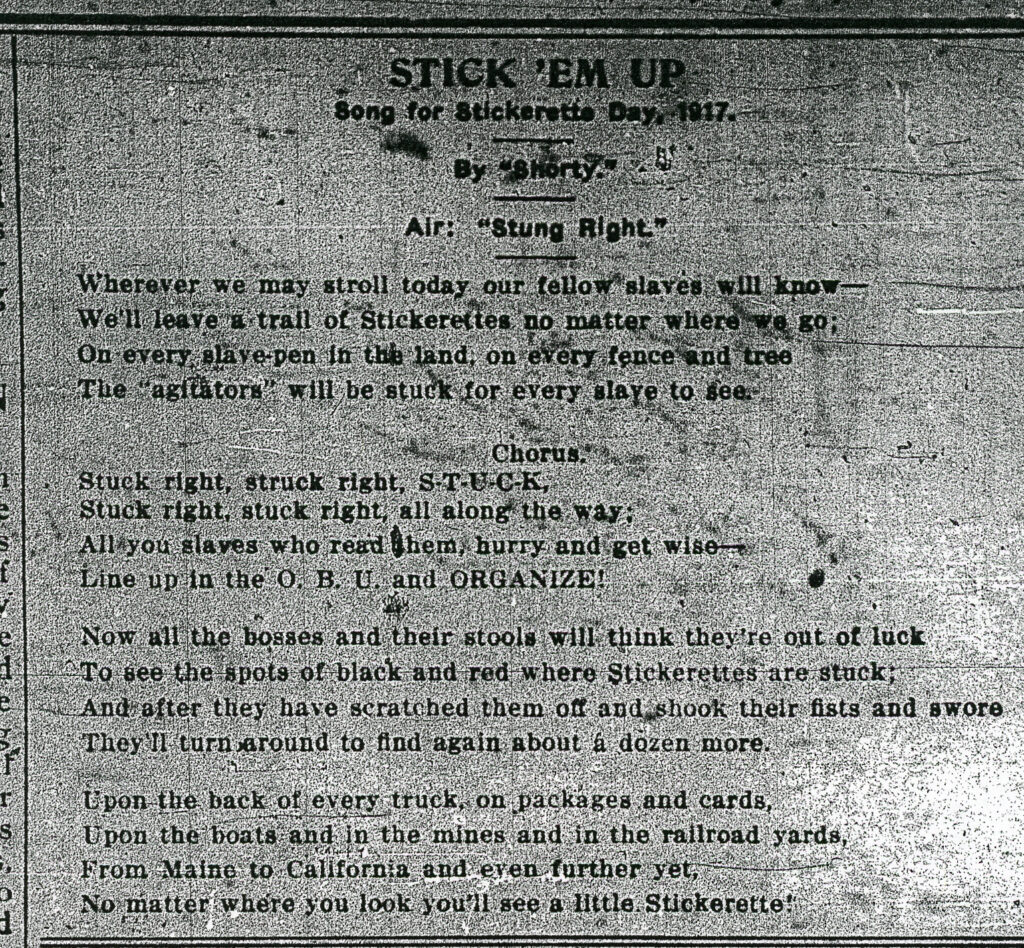

A poem in Solidarity called “Stick ’Em Up” even dubbed April 29, 1917, as “Stickerette Day.” (“Slaves” in this context means fellow workers held down by the ruling class.)

Wherever we may stroll today our fellow slaves will know

We’ll leave a trail of Stickerettes no matter where we go;

On every slave pen in the land, on every fence and tree

The “agitators” will be stuck for every slave to see.

Stuck right, stuck right, S-T-U-C-K,

Stuck right, stuck right, all along the way;

All you slaves who read them, hurry up and get wise

Line up in the O.B.U. and ORGANIZE!

Now all the bosses and their stools will think they’re out of luck,

To see the spots of black and red where Stickerettes are stuck;

And after they have scratched them off and shook their fists and swore,

They’ll turn around to find again another dozen more.

Upon the back of every truck, on packages and cards,

Upon the boats and in the mines and in the railroad yards,

From Maine to California and even further yet,

No matter where you look you’ll see a little Stickerette!

Another three million stickerettes were printed for May Day of 1917, with 65,000 in a variety of foreign languages—something to be expected given that the I.W.W. was the only union in the country to welcome immigrants, along with women, Black people, Asians, Jews, and other marginalized groups.

Union member, poet, and commercial artist Ralph Chaplin created several early stickerette designs. In his 1948 autobiography, Wobbly: The Rough-and-Tumble Story of an American Radical, he recounts that during the peak of the I.W.W. propaganda campaigns (1915-1917), stickerettes could be found on “every boxcar in the country,” as well as “‘skid-road’ flophouses, lampposts, and billboards, [and] such minor items as pitchforks, pick handles, shovels, bunkhouses, factory gates, and even jail houses, all of which were generously decorated with I.W.W. colors and ideas.”

Stickerettes are also mentioned in an essay entitled “Here Come the Wobblies!” by Bernard A. Weisberger for the American Heritage, where he paints a lively picture:

“The I.W.W. reached [the migrant worker] where he lived: in the hobo ‘jungles’ outside the rail junction points, where he boiled stew in empty tin cans, slept on the ground come wind, come weather, and waited to hop a freight bound in any direction where jobs were rumored to be. The Wobblies sent in full-time organizers, dressed in the same caps and windbreakers, but with pockets full of red membership cards, dues books and stamps, subscription blanks, song sheets, pamphlets. These job delegates signed up their men around the campfires or in the boxcars (‘side-door Pullmans’ the migrants called them), mailed the money to headquarters, and then followed their recruits to the woods, or to the tents in the open fields where the harvest stiffs unrolled their bindles after twelve hours of work in hundred degree heat without water, shade, or toilets. But there were some whom the organizers could not reach, and the I.W.W. sent them messages in the form of ‘stickerettes.’ These ‘silent agitators’ were illustrated slogans on label-sized pieces of gummed paper, many of them drawn by Ralph Chaplin.

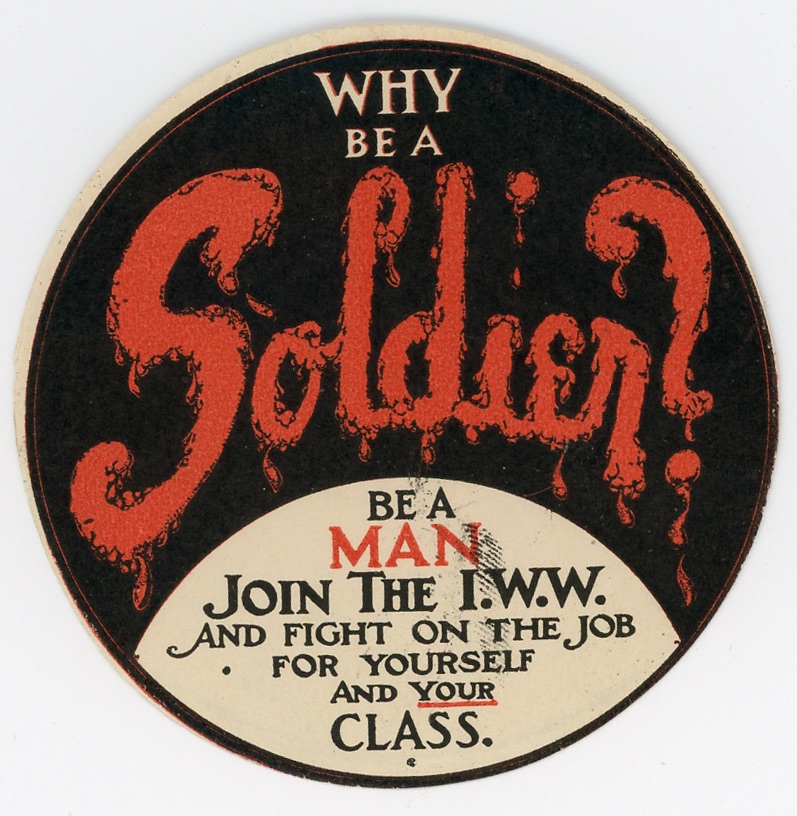

As the United States entered into World War I, many in the I.W.W. considered American involvement to be a capitalist scheme to enrich the elite while sacrificing the working class on foreign soil. Chaplin became editor of Solidarity and printed anti-conscription and anti-war editorials and cartoons from March through September 1917, as well as stickerettes like “Why Be a Soldier? Be a Man — Join the I.W.W and Fight on the Job for Yourself and Your Class.” On September 5, 1917, the federal government simultaneously raided I.W.W. office headquarters and meeting halls across the country, leading to the arrest of 184 union members on charges of interfering with the war effort and sedition under the Espionage Act of 1917, passed only months beforehand. Chaplin himself was arrested and served five years of a 20-year sentence at Leavenworth Penitentiary, though he continued to write and draw while behind bars.

The Espionage Act was passed just after the United States entered World War I. The New York Tribune ran an article, “I.W.W. Beaten in Two Attempts to Rule Out Evidence: Judge Permits Introduction of Pamphlets to Prove Sabotage” (May 7, 1918, p. 7), which described:

“William Cahill, member of a job printing establishment in Chicago, testified that he had printed more than 1,500,000 stickerettes for the I.W.W. These were designed by Ralph Chaplin, one of the defendants, whose pen name is ‘Bingo.’ Many of them advocated sabotage.”

For more information:

- Tony Bubka, “Time to Organize: IWW Stickeretts [sic],” in The American West, January 1968: 21-28, 73.

- Ralph Chaplin, Wobbly: The Rough-and-Tumble Story of an American Radical (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1948).

- Jeffory A. Clymer, America’s Culture of Terrorism: Violence, Capitalism, and the Written Word (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- Greg Hall, Harvest Wobblies: The Industrial Workers of the World and Agricultural Laborers in the American West, 1905-1930 (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2001).

- Joyce L. Kornbluh, ed., Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology (Oakland: PM Press, 2011).

- Mark W. Van Wienan, Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- Bernard A. Weisberger, “Here Come the Wobblies,” in American Heritage, June 1967: 30-35.