My Father’s MLK Cassette Tapes

- Published

- in all

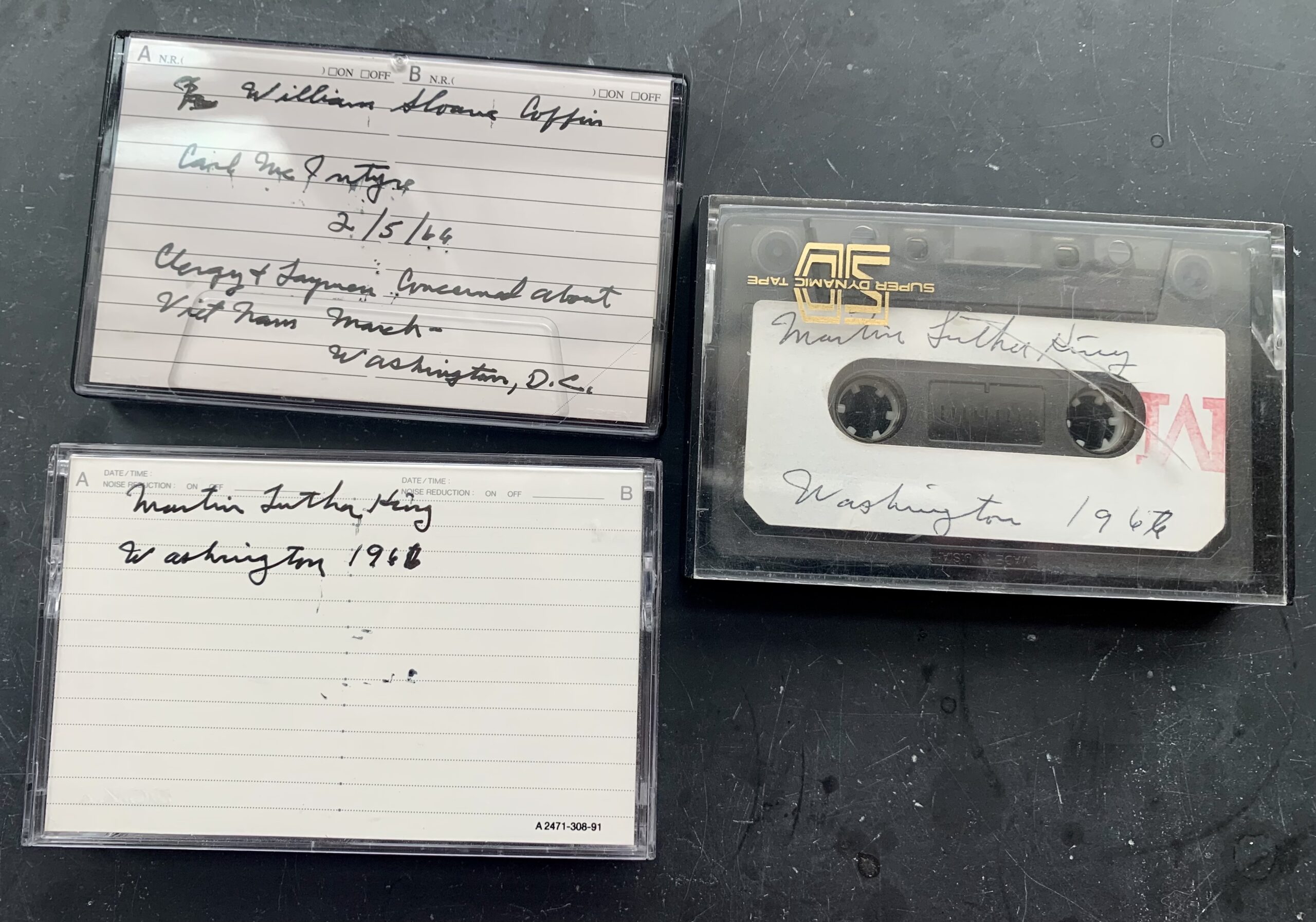

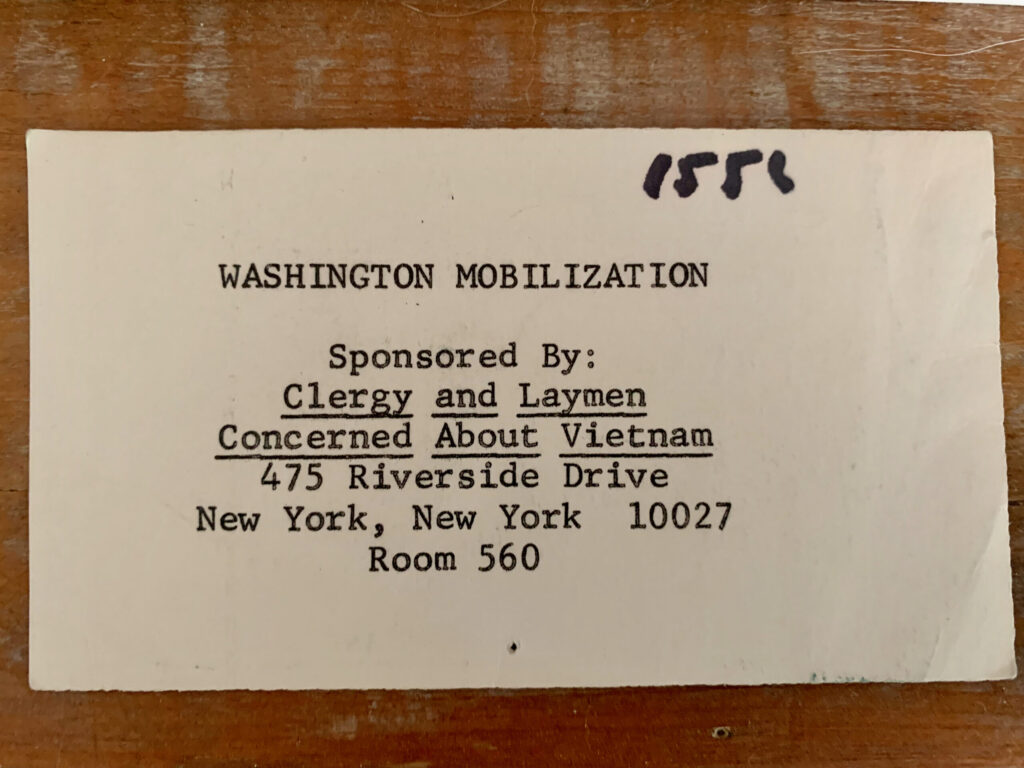

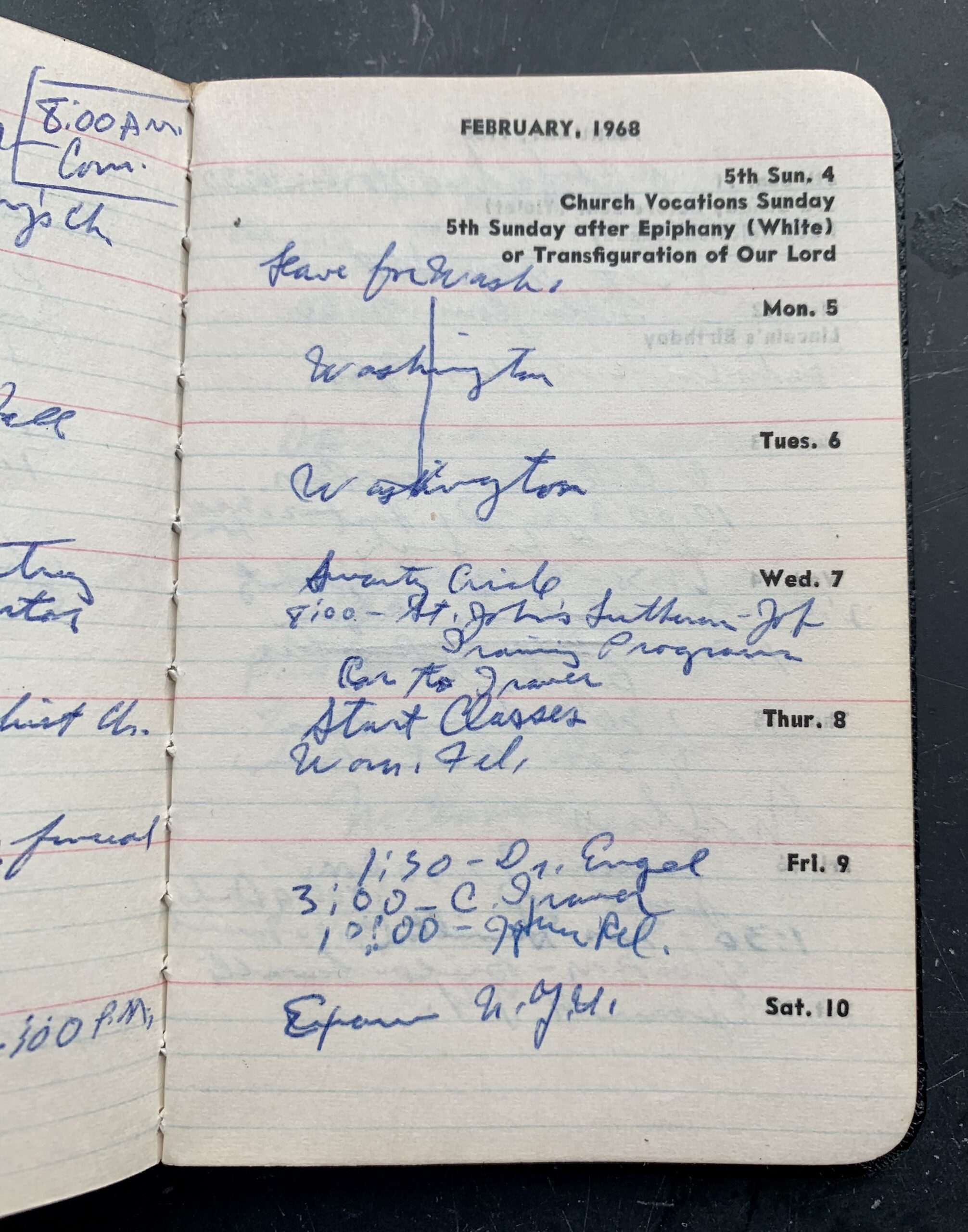

Several years ago, my stepmother gave me my father’s papers after he died in 2008, documenting his involvement in the US civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements in the 1960s and ’70s. In 2019, she sent me another box, and this one included three cassette tapes. Two are marked “Martin Luther King, Washington 1967” (though the 7 in each date is crossed over with a 6). The third tape is marked “William Sloane Coffin, Carl McIntyre 2/5/66, Clergy & Laymen Concerned About Vietnam March – Washington, D.C.” This past month, I started to transcribe one of the tapes, and here is what unfolded.

Influences at Yale Divinity School

[Note: The information in italics below comes from an interview between my father, Rev. Dr. Duane Warner Smith, and my sister, Jean (Smith) Cunningham, for StoryCorps in NYC on December 27, 2006.]

My father went to Yale Divinity School from 1953-57, drawn there, he said, by some of the “theological giants of the 20th century, the Niebuhr brothers [Reinhold and H. Richard] and Paul Tillich and Rudolf Bultmann.” As a kid, I also remember my father telling me about two of his Yale classmates, William Sloane Coffin and Harvey Cox, both of whom influenced and shaped him as a young man. From the StoryCorps interview:

Jean: And then on to Yale. What was that like?

Duane: On to Yale. I went on to Yale in ’53. It was mind blowing. Just absolutely mind blowing. I was the most conservative, mid-western Ohio Republican you ever saw. To go there and to be exposed to these theological giants, and to get a whole new life experience in terms of going into New Haven, and mixing with…. I think every student in my class, there were 140 in my class, was a Phi Beta Kappa except me (laughing).

Jean: No intimidation there!

Duane: It just really blew me open. It opened me up so it was a whole new world, a whole new experience. I’m so thankful that I did it and didn’t go to Oberlin [like his brother, Jack, did]. It radicalized me; I have to say that. That’s where I became the rebel, I guess.

Jean: How did that happen? Was that a slow process? Was there someone there who particularly opened your eyes?

Duane: I had the good fortune of spending one year as a roommate of Harvey Cox. I don’t know if you know the name.

Jean: I know the name.

Duane: You know the name from Harvard [where Jean works]. He’s a prominent professor of the divinity school there now, just retired. We had just endless nighttime conversations and talks, and I was also a classmate of Bill Coffin, the head of the anti-war movement. I had the same experience with him. I had many, many conversations with both of them. You just can’t not be influenced by people like this; they’re so powerful in their thinking and so much farther along than I was that that became important to me. That was how I ended up getting into the further troubles later on (laughing).

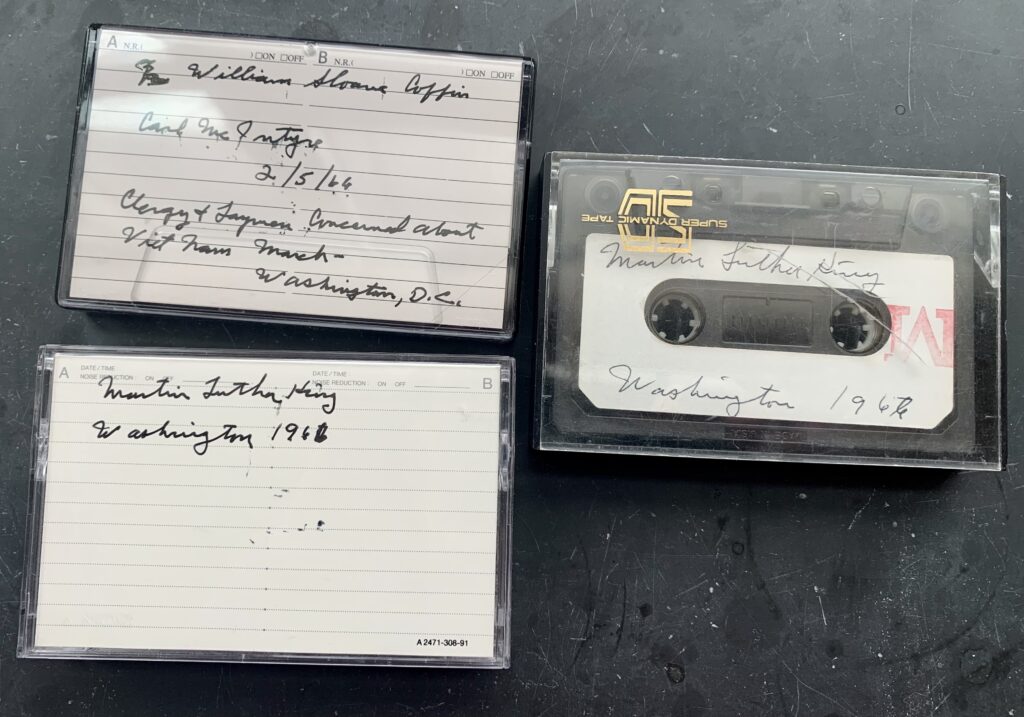

SCLC and CALCAV

After graduating from Yale, my father served at three Congregational churches: First Congregational Church in East Bloomfield, NY (1957 – 1962); Church of the Palms in Delray Beach, Florida (October 1962 – July 1965); and First Congregational Church in Poughkeepsie, New York (September 1965 – 1972). By the early 1960s, he became directly involved in the civil rights movement in the South, and through contact with Coffin and Cox, he became the area coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference “for the gold coast of Florida.” Later in the North, he served as area director for Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam in New York.

Duane: That’s also when I got caught up in the anti-war movement with Bill Coffin. I became the equivalent of that position with a group called Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam. I was the area director for the metropolitan New York area. Not New York City but above, north of New York—Westchester County up. I went on all those marches, and I participated. I became acquainted with Dr. King. Well, I got acquainted with Dr. King in the south in the civil rights movement, but I also got acquainted with him in the anti-war movement when I came up to Poughkeepsie. I really got to know him better up here, up in New York, when he got into the anti-war movement and the Clergy and Laymen Concerned group. Then, it [consisted of] Bill Coffin, Dr. King, Dr. Spock, and Harvey Cox. There were four or five others, very prominent clergymen, who were all heading that movement. They just happened to be classmates of mine, good friends of mine from divinity school.

Notes on the Transcription: Some of the language in the speech transcribed below is very similar to what appears at the beginning of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, delivered on December 11, 1964.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Address Delivered to Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam, February 6, 1968, Washington, DC. He was assassinated two months later on April 4, 1968.

“I need not pause to say to say… how very delighted I am to be here and how delighted I am to be in the midst of this fellowship of Concerned [Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam]. It’s a magnificent experience to see so many of you taking time out of what I’m sure are busy schedules in coming to Washington to make a witness. I need not remind you that these are difficult days in which we live, and in these days of emotional tension when the problems of the world are gigantic in extent and chaotic in detail. The challenge faces us more than ever before. The church and the synagogue to take a stand towards justice and for peace. From a scientific and technological point of view, there can be no gainsaying of the fact that our nation has brought the whole world to an awe-inspiring threshold of the future. We’ve built machines that think and instruments that peer into the unfathomable ranges of interstellar space. We have built gargantuan bridges to span the seas and gigantic buildings to kiss the skies. Through our space ships, we have penetrated oceanic depths, and through our airplanes, we have dwarfed distance and placed time in chains. This really is a dazzling picture of America’s scientific and technological progress.

But in spite of this, something basic is missing. I just want to say a few words about that. This afternoon, in spite of all of our scientific and technological progress, we suffer from a kind of poverty of the spirit that stands in glaring contrast to all of our material abundance. This is the dilemma facing our nation, and this is the dilemma to which we as clergymen and laymen must address ourselves. Each of us lives in two realms in life, the within and the without. The within of our lives is that realm of spiritual ends expressed in art, literature, morals, and religion. The without of our lives is that complex of devices, techniques, mechanisms, and instrumentalities by means of which we live. The problem we face today is that we have allowed the within of our lives to become absorbed in the without.

Henry David Thoreau said, once, something that still applies. In a very interesting dictum, he talked about improved means to an unimproved end. And this is the tragedy, that, somewhere along the way as a nation we have allowed the means by which we live to outdistance the ends for which we live, and consequently we suffer from a spiritual and moral lag that must be redeemed, if we are going to survive and maintain a moral stand.

Now nothing convinces me more that we suffer this moral and spiritual lag than our participation as a nation in the war in Vietnam. Our involvement in this cruel, senseless, unjust war is a tragic expression of a spiritual lag of America, and this is why we must be concerned about it on a continuing basis. I need not go into a long discussion about the war and its damaging effects we all know. We know that the war in Vietnam has destroyed the Geneva Accord. We know that the war in Vietnam has strengthened the military industrial complex of our nation. We know that the war in Vietnam has strengthened the forces of reaction in our nation. We know that the war in Vietnam has exacerbated the tensions between the continents, between the races.

It does not help for America and for our so-called image to be the most powerful, richest nation in the world, at war with one of the smallest, poorest nations in the world that happens to be a colored nation. And this is something that must be said over and over again—for a predominantly white nation to be at war with one of the smallest, poorest nations that happens to be a colored nation, only leads a nation, leads America, to a point of losing its own soul, this country isn’t done.

But not only that. The war in Vietnam has played havoc with our domestic destiny. We would think about the fact today that our government spends about $500,000 to kill every Vietcong soldier, while we spend at the same time about $53 a year per person for everybody characterized as poverty stricken in the so-called war against poverty, which isn’t even a good skirmish against poverty.”

[Audience clapping.]

“We can look all around and see how we find ourselves with mixed up priorities. President Johnson raised a question the other day, the other night, rather, when he was giving his State of the Union address. He talked about the seventy million televisions in our country. He talked about the beautiful highways and all the beautiful new cars, about eight million a year that’s going down these highways. He talked about our material abundance, and then he said something that needs an answer. He went on to say yet there is so much restlessness in the land. He said there is so much questioning. Now I would like to say there is restlessness in the land because the land doesn’t seem to have a sense of purpose, a proper sense of politics and a proper sense of priorities.”

I stopped transcribing here because that last sentence carried a pretty big punch that warranted a Google search. I discovered that it came from an address delivered in Washington, DC, on February 6, 1968, to Clergy & Laymen Concerned About Vietnam (CALCAV) entitled A Proper Sense of Priorities. That was the event my father attended in DC, in which he was able to record Martin Luther King, Jr.! You can read the rest of the speech on the link provided above.

I still can’t figure out why my father put 1966 or 1967 on the cassette tapes, however, since the recording transcribed above was clearly MLK’s address to CALCAV in February, 1968. My father’s daily calendar from that time period also shows that he was in DC for this event. Maybe something else will turn up to help explain it.

In any case, I contacted the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia, last week, to see if I could donate the tapes to them. A woman named Cynthia Lewis from the King Library & Archives called me right back and said yes. So, my father’s MLK tapes will be going to a good forever home that others can use for teaching and research. That’s been my goal all along.

UPDATE 4.18.21

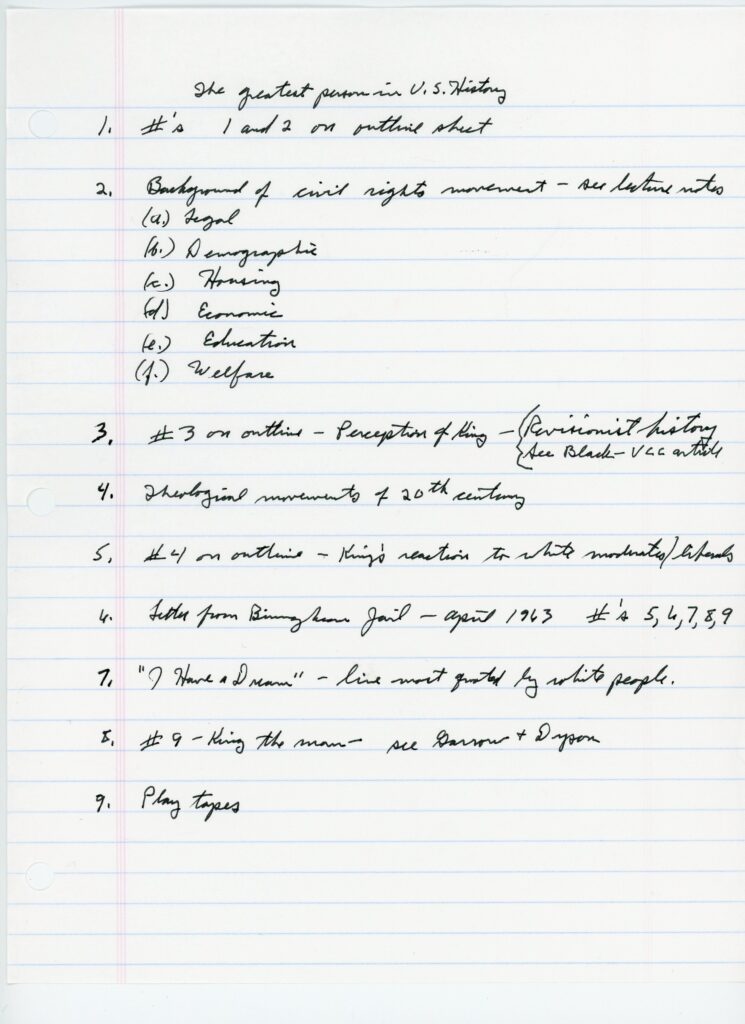

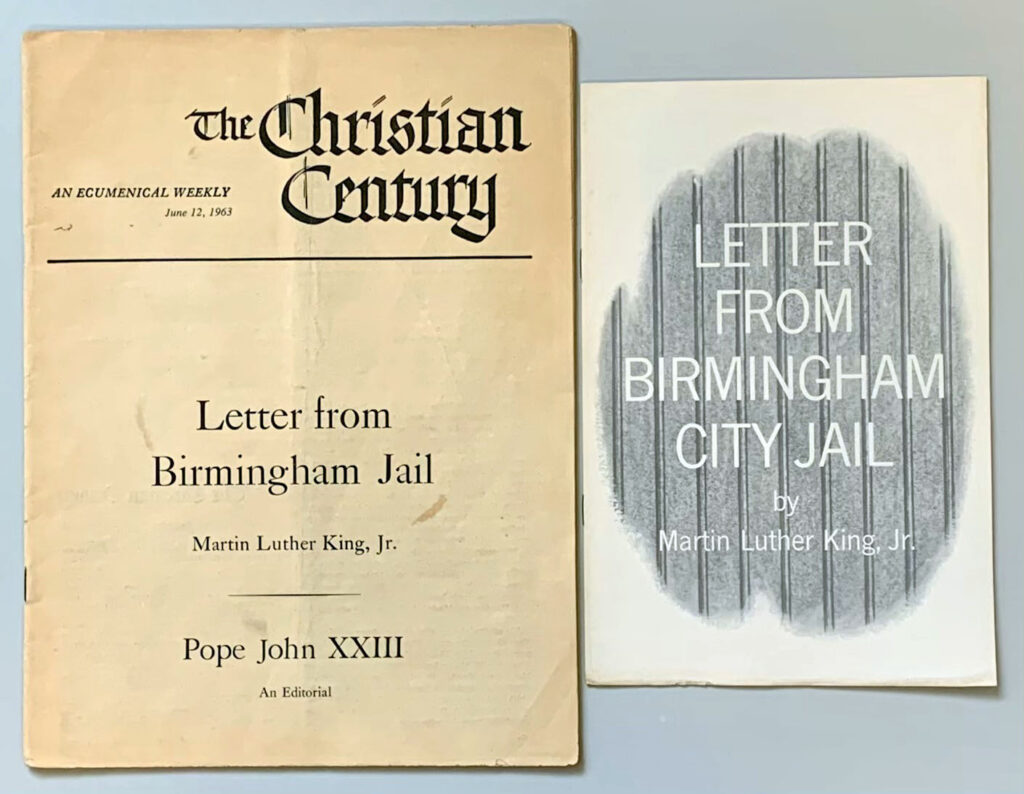

I asked my stepmother about the incorrect dates on the tapes, and she told me that my father made several copies of the MLK tapes to bring to Dutchess Community College and to Green Haven Correctional Facility, where he taught the Sociology of Religion from 1972 to his retirement in 2000. He must have lectured on King on a regular basis, because I also found this in my father’s papers.

Also, the King Center has not returned my email, which is odd given their initial interest. At the suggestion of archivist Steven Booth, I’m going to reach out to “the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at BU and the AUC Woodruff Library, which is the physical custodian of the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection.” I had heard Steven give a fantastic keynote lecture in March for the 2021 Visual Resources Association conference, in which he talked about connecting people together through archival work. It turns out that his first professional job was working on King papers between these two institutions, so I’m glad I contacted him. Stay tuned!

**One more interesting item to point out: the recording that my father made of A Proper Sense of Priorities has additional remarks from MLK at the beginning of his speech than what is transcribed on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website, as follows:

“I need not pause to say to say… how very delighted I am to be here and how delighted I am to be in the midst of this fellowship of Concerned (Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam). It’s a magnificent experience to see so many of you taking time out of what I’m sure are busy schedules in coming to Washington to make a witness. I need not remind you that these are difficult days in which we live, and in these days of emotional tension when the problems of the world are gigantic in extent and chaotic in detail. The challenge faces us more than ever before. The church and the synagogue to take a stand towards justice and for peace. From a scientific and technological point of view….”

Other Civil Rights and Anti-Vietnam War Links