Chapter proposal: Street Art Stickers as Subversive Visual Discourse

- Published

- in "The Process is the Product", all, Visual literacy

A chapter proposal that I submitted for a new anthology was recently accepted! Entitled Unframing the Visual: Visual Literacy Pedagogy in Academic Libraries and Information Spaces, the volume will be published as a companion piece to the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education (2016). The new collection features four sections: participating in a changing visual information landscape; perceiving visuals as communicating information; practicing visual discernment and criticality; and pursuing social justice through visual practice. My proposal was accepted for the section on pursuing social justice through visual practice.

My chapter proposal

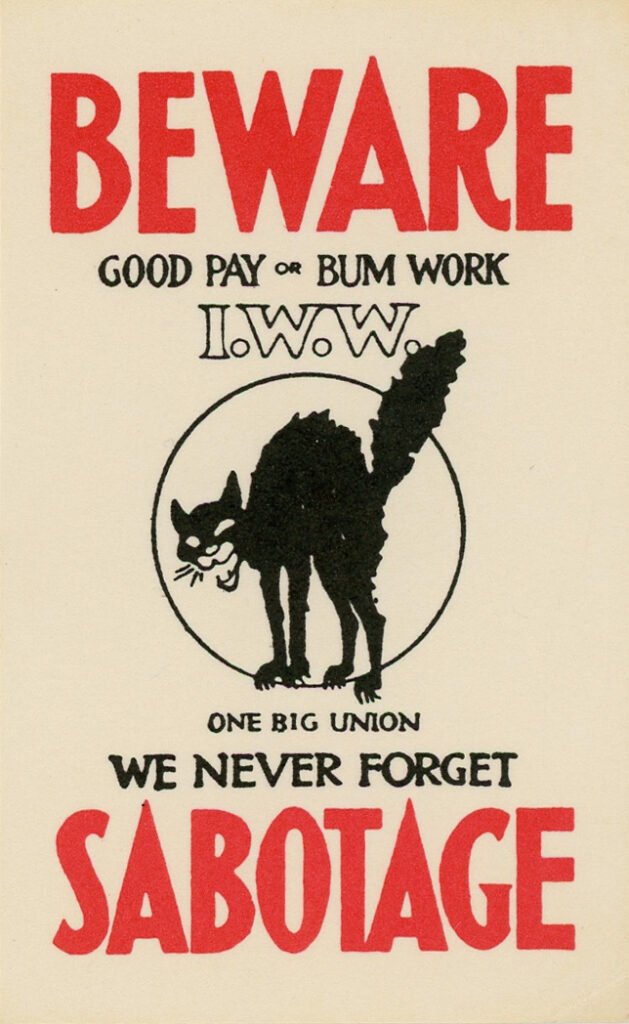

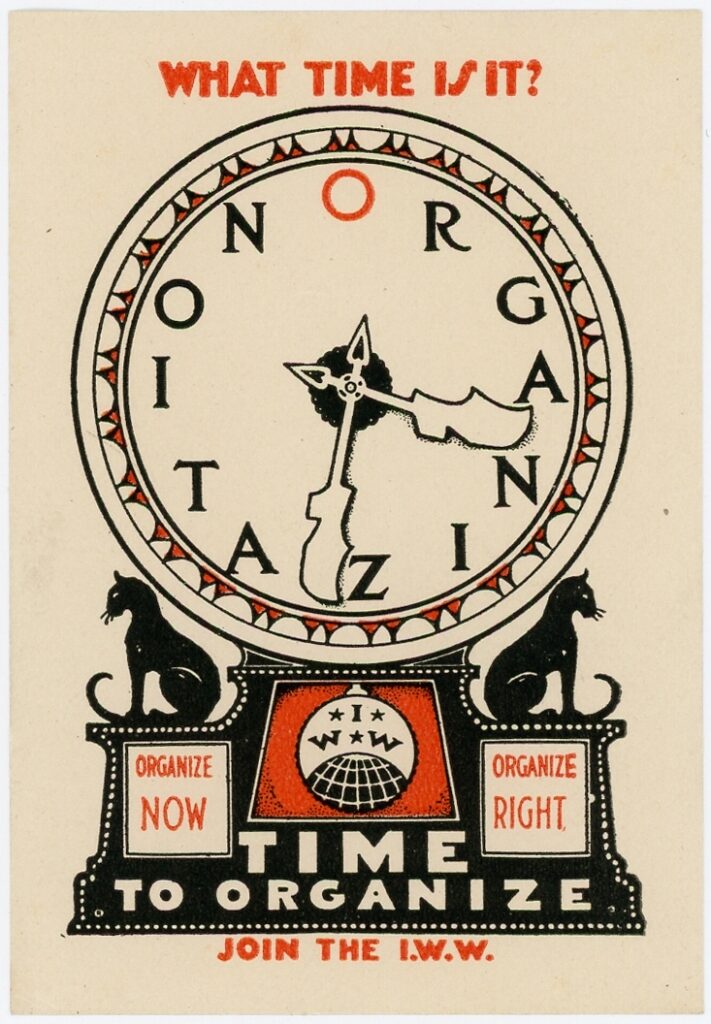

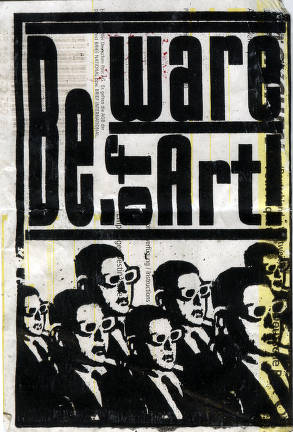

Publicly-placed stickers with printed images and/or text have been used for decades around the world as a means of creative expression and as a provocative way to engage passersby. In the United States as early as the 1910s, for example, the Industrial Workers of the World created the first “stickerettes,” or “silent agitators,” to oppose poor working conditions, intimidate bosses, and condemn capitalism.

Today, stickers may be used to “tag” or claim a space and make it temporarily one’s own, to sell products or services, to announce events, to publicize blogs and social media sites, or to offer social commentary and political critique. As one of the most democratic art forms, stickers can be created and distributed easily, quickly, cheaply, and widely.

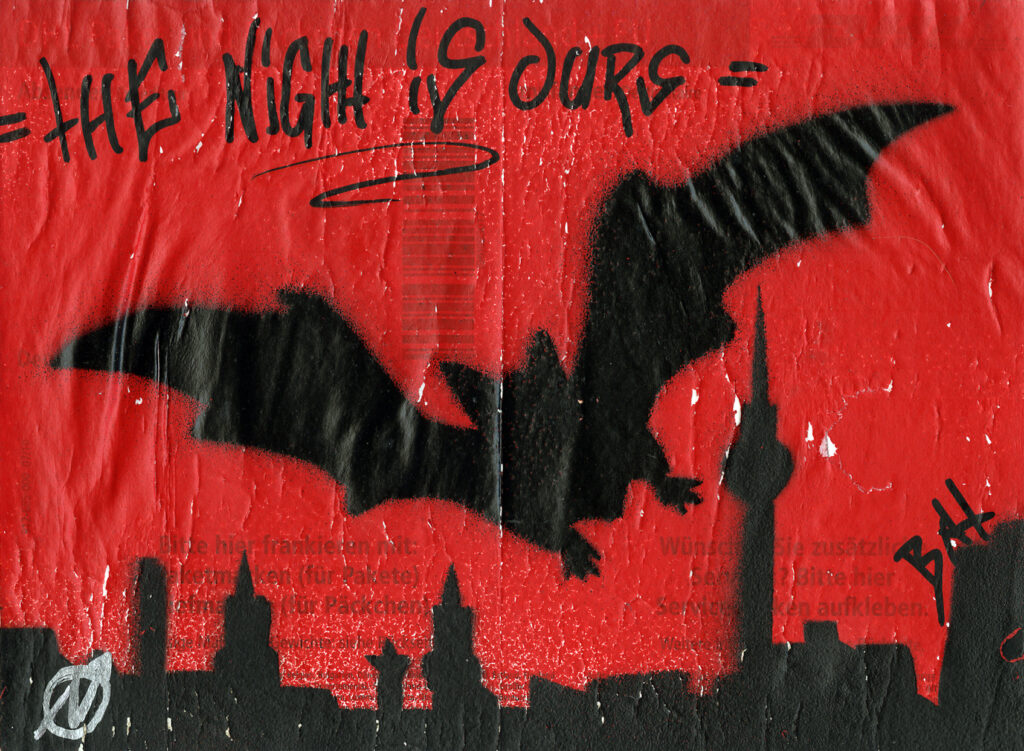

Inherently subversive in their creation, content, and placement, stickers offer a lively “ground up” alternative to the monolithic “top down” commodification of most Western capitalist societies. Slapped on street signs, light poles, and dumpsters, stickers “talk back” to authority, asking us to pay attention. Some stickers shout; others whisper. But, as noted in the exhibition “THE ABC: power and communication/the semiotics of resistance” (Berlin, 2005), “…unlike graffiti, […] stickers don’t have the gesture of destruction inherent in their form – [rather, they are a] gesture of connotation and satiric annotation. [Sticker] interventions are much more representative for a critical mind seeking to contribute to the social urban exchange….”

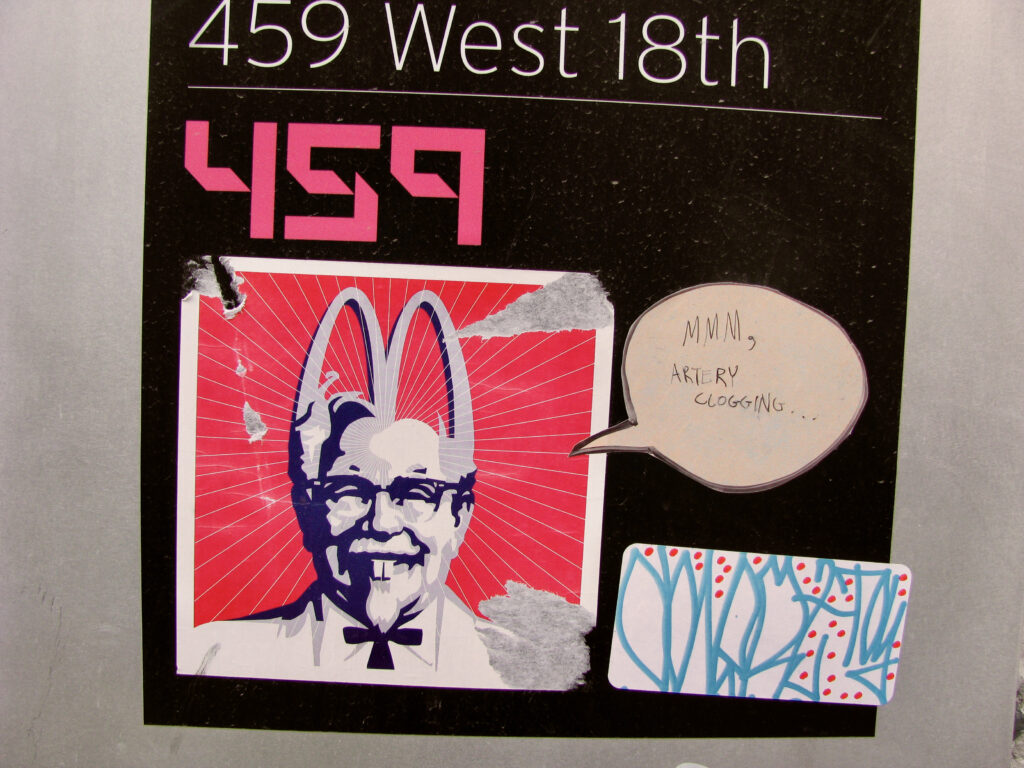

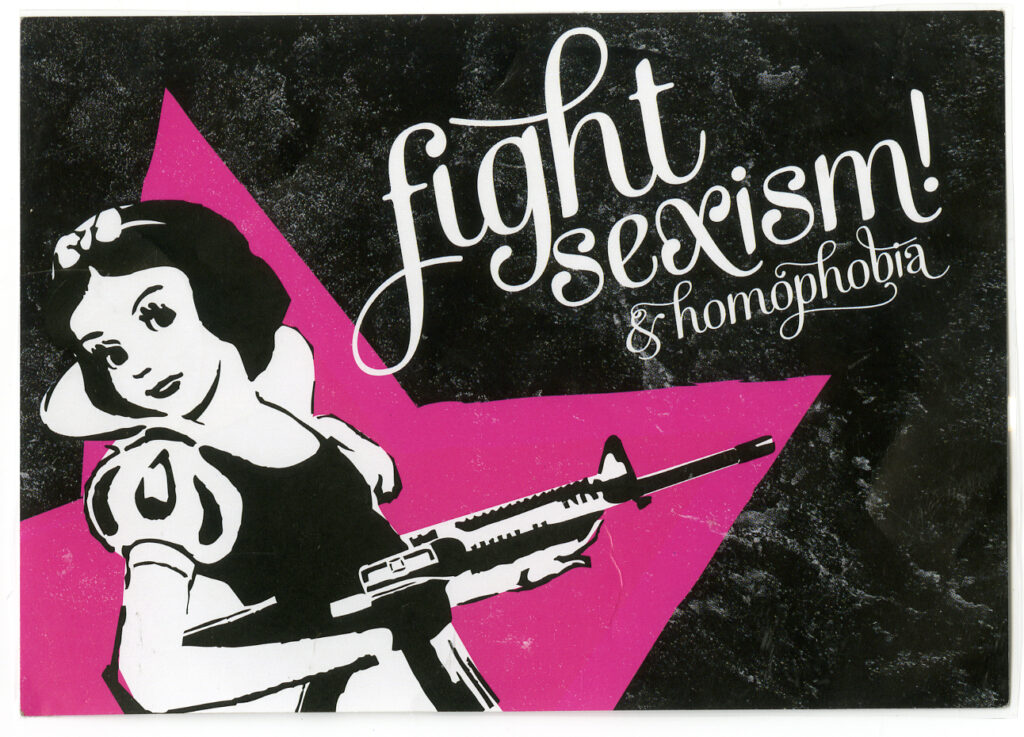

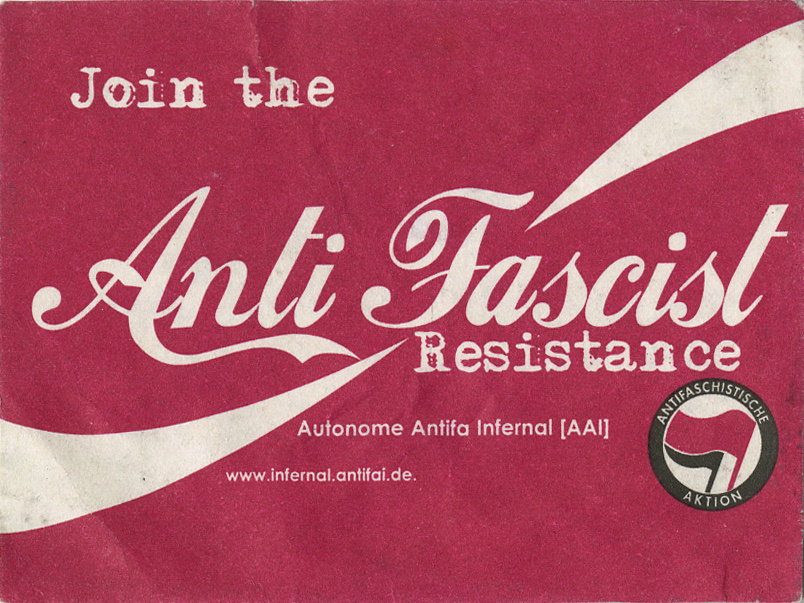

The chapter begins with an overview of street art stickers and includes more in-depth analysis of how sticker artists engage in “culture jamming,” whereby images from pop and consumer culture are appropriated as memes and subverted in order to create new meanings. Examples include Bart and Lisa Simpson in German antifa stickers, Snow White fighting sexism & homophobia, and the Nike “swoosh” in a variety of sociopolitical contexts.

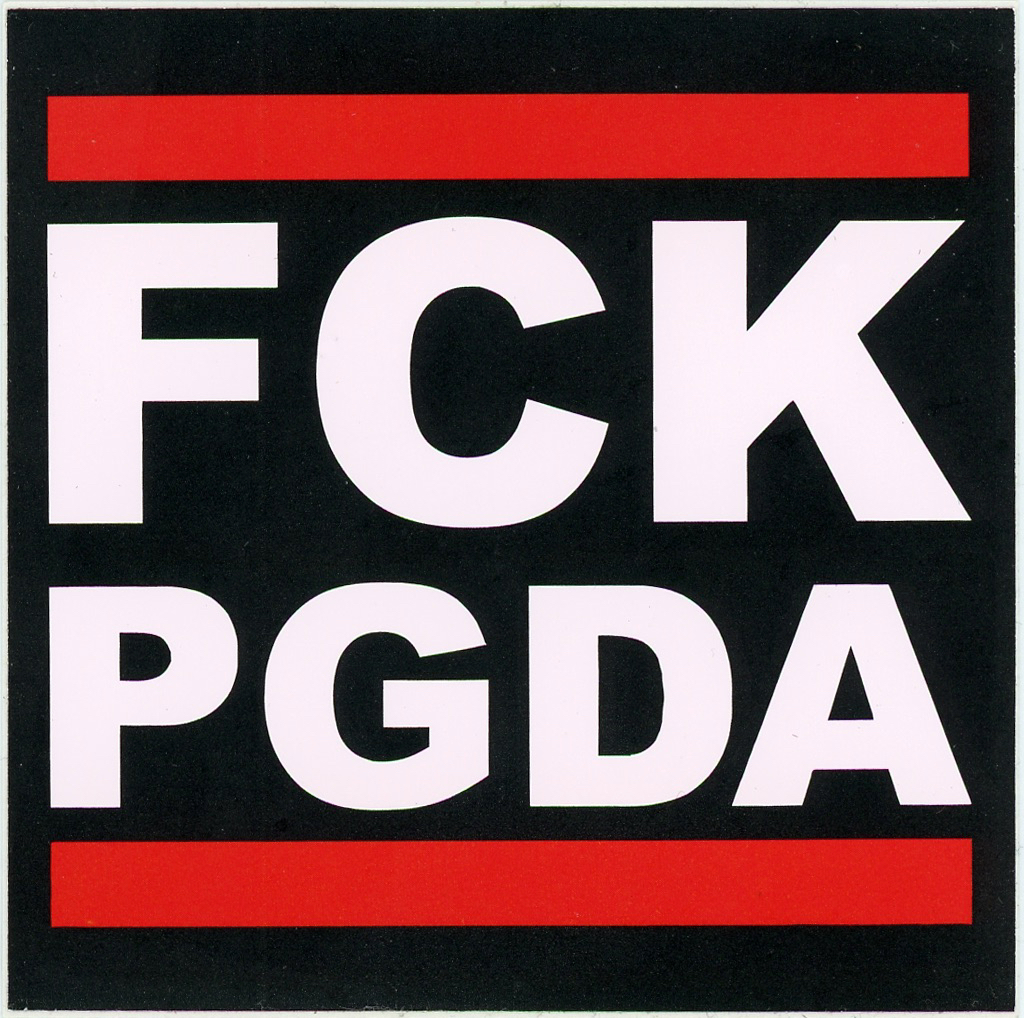

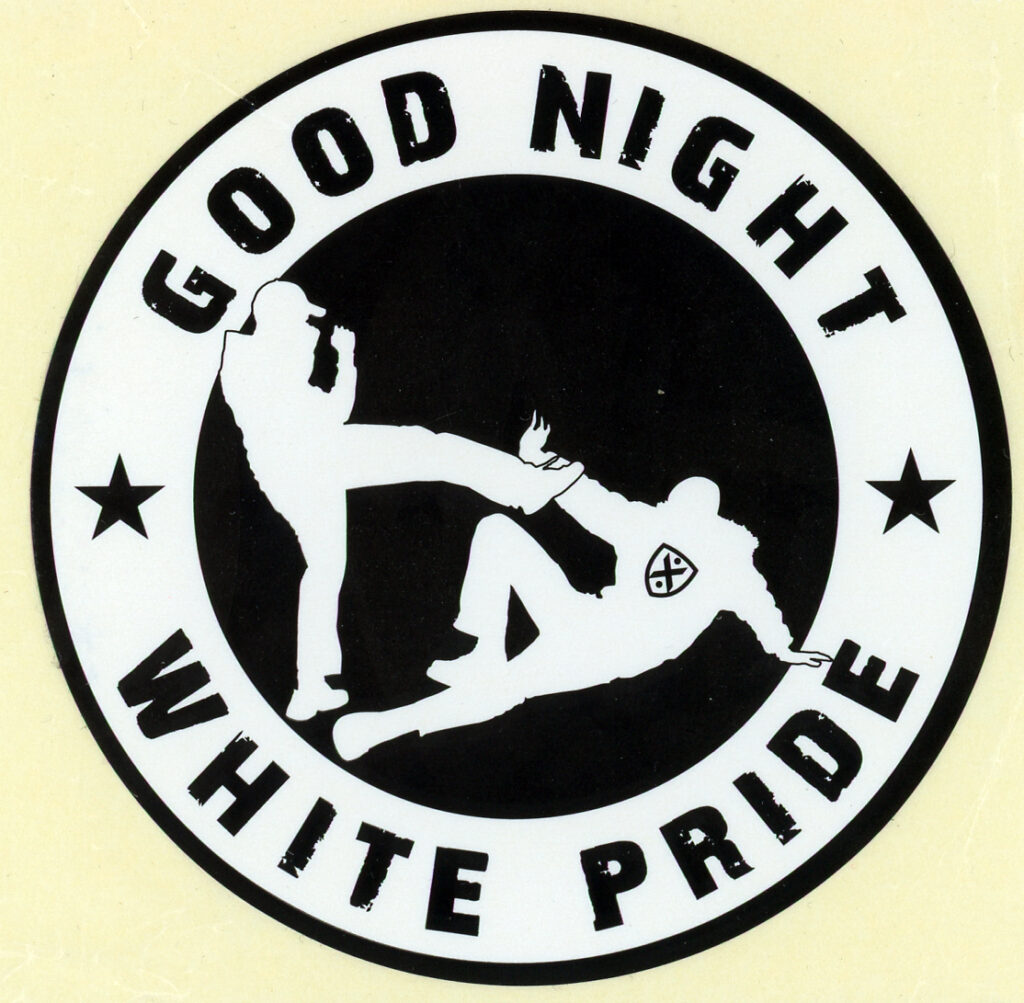

Other examples riff on the RUN-DMC logo, “Hello-My-Name-Is” labels, and “Good Night White Pride” designs.

I am personally most interested in political stickers and could discuss the use of stickers that address issues such as urban development/gentrification, race/class/gender, the environment, police brutality, immigration, nationalism, and technology/surveillance, among other topics. To see stickers like these grouped by geographic location and theme, go here. These were the stickers I showed in Berlin, Germany, in 2019 for an exhibition from my collection called Paper Bullets: 100 Years of Political Stickers from Around the World.

Learners pursue social justice through visual practice

The editors of the book asked that contributors consider the ACRL’s Framework for Visual Literacy, and especially the section on social justice (at the bottom of this link). Here is an excerpt:

Visual practice is the creation and consumption of visuals for the purpose of transmitting and building knowledge. The pursuit of social justice through visual practice is an ongoing journey, which requires consistent work related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Pursuing social justice can include decentering whiteness, heteronormativity and other hegemonic practices in visual collections and canons, improving accessibility of visuals and platforms, and opposing exploitative practices that deprive visual creators of intellectual property control or Indigenous communities of sovereignty. Visual literacy learners understand that pursuing social justice through visual creation, sharing, use, remix, and attribution takes continual effort and education. By building reciprocal relationships with communities, acknowledging the limits of their own knowledge, and seeking to better understand their worldviews, biases, and perceptions, as well as those around them, learners can become conscientious contributors to a more just world.

With that in mind, the editors also suggested the following questions to help frame my chapter:

- How do these stickers move people to action?

- How do creators think through the creation process (from format to placement in urban areas) in order to create social impact?

- What other considerations must readers understand about the graphics, fonts, messaging, images, of these stickers?

- What is the value of these stickers beyond their immediate social-political-temporal context?

- What conversations, if any, occur among creators and the communities they live in (reception, reaction, impact, etc.)?

My editor, Stephanie Beene, also wrote, “The editors were especially interested in your discussion of political stickers that address issues such as urban (re)development and gentrification, intersectional identity (e.g., race, ethnicity, nationality, class, gender, sexual orientation), environmental justice issues, police reform and public safety concerns, immigration and human rights, and surveillance concerns. This will be one of the theoretical chapters, amply illustrated with color illustrations.”

That’s a lot to digest, isn’t it? Part of the challenge here for me will be to write this without sounding too academic. #nojargon #keepitreal #connect

Cathy, you are boss!! This fantastic. Congratulations on furthering the dialogue on ‘art as change agent’s. Kudos!!